In recent weeks, governing bodies in two counties in East Tennessee failed to adequately notify the public of meetings in which they were taking up issues of high public interest.

The lack of adequate public notice of meetings is a violation of the Open Meetings Act. The failure of local government entities to follow the law suggests either an irresponsible lack of understanding of the law or a willful flouting of it in an effort to exclude the public from knowing about government business. Both are egregious.

The first example was in Loudon County when members of the Loudon County Board of Education were called to a special meeting on Aug. 31 by the schools director to discuss changes and “come to a consensus” on the school board’s open records policy. (If there is any doubt about the purpose of the meeting or that members of the school board deliberated about public policy, there is a video to prove what happened.)

No public notice was given of the meeting. School board director Jason Vance claims the meeting was not a meeting subject to the Open Meetings Act because there was no written agenda and no vote taken.

The second was in Greene County when the Greene County Health and Safety Committee met on Sept. 6 to respond to citizen calls for enforcement of environmental regulations against US Nitrogen. The plant has stirred controversy among citizens since land was rezoned to build it, and citizen activism by Indivisible Greene County pushed the county government to schedule a meeting to discuss what could be done about environmental violations. The citizens most interested in the county’s followup committee meeting did not find out about it until after the meeting had taken place. The only notice of the meeting was given on a single AM radio station.

In both cases, the public was not given a fair chance to know about the meetings.

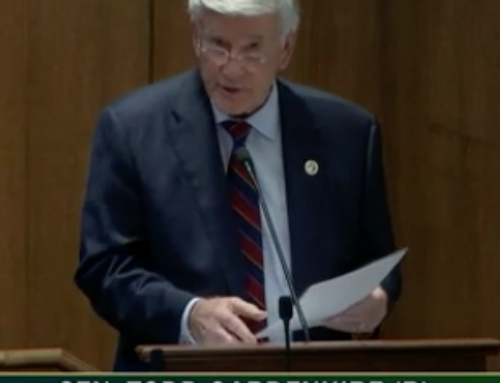

A video of the Loudon County Board of Education meeting which the schools director said was to “gain consensus” over what should be in the public records policy.

In the case of the Loudon County Board of Education, the chairman of the school board alerted a citizen who had previously expressed great interest in the public records policy and invited her to attend. But no one let the local newspaper know, and no notice was posted anywhere of the meeting.

Jonathan Herrmann of The News-Herald in Loudon County reports about the possible violation of the Open Meetings Act in Loudon BOE meeting in question. And a followup editorial by the newspaper raises additional questions about whether this practice of pre-meetings to “gain consensus,” as the schools director put it, is a pattern. (Keep meetings in the open).

A citizen, Richard Truitt, has filed a lawsuit against the Board of Education for a violation of the Open Meetings Act. He is represented by attorney Linda Noe.

In Greene County, citizens who are part of a Indivisible Greene County, have complained that a meeting of the county government’s health and safety committee to discuss US Nitrogen was held without adequate notice. The county notified the radio station, who mentioned the meeting on air. It also sent a note about the meeting to a reporter at the Greeneville Sun. The Sun did not write a story advancing the meeting because of a communication breakdown, and apologized to the community. But it emphasized that the only way to assure notice of a public meeting appears in the paper is to buy a legal ad, where many notices of public meetings appear.

The law is clear. As the Greeneville Sun pointed out in its excellent editorial afterward, a three-prong test was established by a state appellate court that provides clear guidance to local government entities for special-called meetings:

• Notice must be posted in a location where a member of the community can become aware of such a notice.

• The contents of the notice must reasonably describe the purpose of the meeting or the action proposed to be taken.

• The notice must be posted at a time sufficiently in advance of the actual meeting in order to give citizens both an opportunity to become aware and to attend the meeting.

It’s time for local government entities in Tennessee to take more seriously their responsibility and stop treating the Open Meetings Act as a suggestion rather than the law.