Release the Covenant crime records: An aware public can help stop additional attacks

The mass shooting at the Covenant School in Nashville has led to an extraordinary legal battle over the public records law and transparency of our criminal justice system.

The school, the church that owns the school and the parents of the schoolchildren are seeking to stop the public from seeing evidence collected by police in one of the most horrific crimes in Nashville in recent memory, saying that it would be too painful and inspire more school shootings.

The parents, school and church aren’t considering that the information might lead to policies that could save other children’s lives. The information also could help inform the public about what to look for to avert future tragedies.

The most ardent fight is over the release of the shooter’s writings, which police found in her car and home and initially described as a manifesto. But access to other information held by police that could shed light on the crime is also at stake.

While it is wrenching to oppose what the grieving parents, school and church want, many of their legal arguments, if adopted by the courts, would turn on its head public access to crime records well beyond this case.

If the shooter were still alive and there was a criminal trial, both the prosecution and the defense would likely seek to enter any evidence that shows the shooter’s motive, communications and state of mind.

When a crime results in no trial — either because the perpetrator died or police chose not to prosecute anyone — police are not then allowed to hide the evidence they collected in their investigation. The public records law allows access, ensuring both accountability of law enforcement for their decisions and a better informed public about crime. The truth is still important.

The legal proposition in the case about the Covenant shooting records would change that: Anyone could stop release of crime information if he or she is a victim of the crime, owns property involved in the crime or has any legal interest in not wanting evidence collected by police to come to light.

For example, in this case, the parents of the 28-year-old shooter have informed the court that they own their daughter’s writings and consider them intellectual property. They don’t want their daughter’s writings released and are transferring ownership to the Covenant children’s parents so they can try to use intellectual property and copyright laws to prevent such release.

This is a novel argument. Think about all the written communications, texts, audio recordings and video that is collected as evidence in a typical crime case. Would this open a new door to keep that evidence confidential?

Should crime evidence be withheld if victims ask for it?

The parents also say that the victims’ bill of rights in the Tennessee Constitution gives them a legal right to stop the release of evidence. And the children and staff are not the only victims who might claim such rights. A declaration filed in court by Nashville police says the police officers who responded to the shooting, the school and the church also qualify as victims under the law.

The Tennessee Constitution says that victims have the right to be “free from intimidation, harassment and abuse throughout the criminal justice system,” a clause that is most often considered to protect victims during criminal proceedings from the defendant.

The Covenant parents argue that the release of the shooter’s writings will allow the shooter to “abuse, harass, and intimidate the children from beyond the grave, for the rest of their lives” in violation of these rights.

They, along with the church and school, also argue that the shooter’s writings will inspire additional school shootings — copycat killers. This is the argument that I think gives us most pause because no one wants more shootings.

But keeping confidential information about school shooters as a way to stop others is contrary to findings by our own government that indicate that one of the most important factors in stopping attacks is a public that is aware of warning signs.

Knowing warning signs can help stop shootings

The top finding in a 2021 report by the U.S. Secret Service and the Department of Homeland Security, “Averting Targeted School Violence,” was that “targeted school violence is preventable when communities identify warning signs and intervene.”

In all 67 averted school attack plots from 2006 to 2018, “tragedy was averted by members of the community coming forward when they observed behaviors that elicited concern,” the report said.

Parents and families play a crucial role in addressing a student’s risk of causing harm, the report found. Students displaying an interest in hate-filled topics should “elicit immediate assessment and intervention” and removing the student from the school does not eliminate the risk.

Significant to all of us, most would-be killers communicated their intent to attack in some way ahead of time, the report said.

In this case, the killer had long since left the Covenant school she attended as a child but still lived at home with her parents.

People undoubtedly wonder whether the shooter exhibited any signs or communicated her plans. We know from police that the shooter began buying guns in 2020. But we don’t know much more.

Could she have been stopped?

Isn’t that the essential question that involves all of us? What can we learn from what she wrote, what she did and what she told others that can make us more aware, help us intervene and stop this from happening again? What resources such as additional security and emotional care should be available to prevent future killings?

The parents, church and school claim that the public interest in what police have discovered is simply “voyeuristic” or “political” and that additional information doesn’t matter because the shooter is dead, killed by police when they stormed the school. I disagree.

The public has a right to know more about the crime than what the parents, school and church consent to. While they assert no one has a greater interest than they do, they do not have the only interest. We all want to stop school shootings.

We learn from experience. We learn from knowledge. We don’t learn when, in the pain and grief, we bury the facts as we bury our dead.

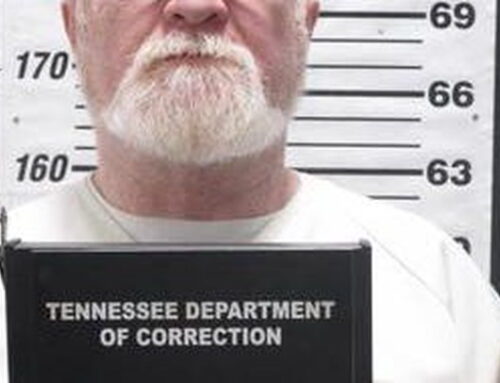

Deborah Fisher is executive director of Tennessee Coalition for Open Government. Police said that they believed the shooter was transgender. Because the shooter’s mother referred to the shooter as her daughter in a comment to the news media, I have referred to the shooter with female pronouns for the sake of not confusing the reader.