Police, ACLU, open government advocates talk body cam footage

Representatives from police, the ACLU, the Tennessee Coalition for Open Government, the Tennessee Press Association and one of the largest vendors of body cams offered thoughts today to the state Senate Judiciary Committee on the use of body cameras to record interactions between law enforcement and citizens.

Several police departments are moving forward with plans to equip their officers with body cameras, raising issues of how the cameras will be used, how long video will be retained and what is releasable under the state’s public records laws.

See video: Hearing on body camera footage before the Tennessee State Senate Judiciary Committee (Body cameras start at 2:45)

The Knox County Sheriff’s Office, for example, has deployed 100 body cameras to deputies, and plans to roll out another 100 with 225 eventually wearing the cameras to record interactions. In Memphis, the police department plans to issue 2,000 body cameras to officers, said Deputy Chief Jim Harvey.

Many spoke of the virtues of the video, including the representative from TASER, Inc., which sells them, who cited studies in California saying they reduced officer use of force. He said the “ROI” for cameras was that less time was spent in internal investigation, the ability to have better evidence (“digital evidence”) of an interaction, and improvement of community trust. All the cameras that TASER sells include an add-on cloud storage capacity for the video at $15 to $75 per officer per month, said the TASER representative, Isaiah Fields. He said that officers see the video as “legal body armor.”

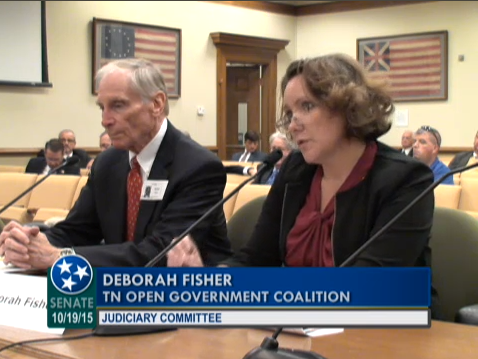

TCOG Executive Director Deborah Fisher makes the point that police should not be the sole arbiters of which footage from body cameras the public is allowed to see.

But Fields noted that one of the biggest issues that prevent police from buying and implementing body camera technology is that it creates records that are subject to state public records law. Sometimes that means that local police agencies must spend time redacting video to comply with any confidentiality requirements of the public records law before they can release the video.

Lt. Aaron Yarnell of the Knox County Sheriff’s Office said that it implemented its first 100 cameras, and has not had a lot of open records requests. In Memphis, Harvey said he expects 2.5 hours per day per officer of video to be produced. Harvey cited a recent records request for dash cam video from 2015, and said it would drain the resources of the city to provide all of that video to the requester.

Knoxville Police Chief David Rausch, who is also president of the Tennessee Association of Chiefs of Police, said he was concerned about release of video that might be recorded from inside someone’s home.

Hedy Weinberg, executive director of the ACLU-Tennessee, said they favored body cameras, but also wanted rules that would ensure citizen privacy as well as police officer accountability and transparency was included in any legislation to make sure that uniform practices existed throughout the state. The ACLU has published a policy paper on how to balance accountability and transparency: Police body-mounted cameras: With right policies in place, a win for all.

Tennessee Coalition for Open Government advocated that it would be concerned about a broad exemption to the Tennessee Public Records Act regarding body cam footage, or an effort to make release of the footage at the sole discretion of law enforcement officers.

“In other words, if police departments and law enforcement become the sole arbiters of what video the public gets to see, the purpose of the body cameras is lost for the public. The public would come to view body cams as simply another surveillance tool, or a propaganda tool, ” said Deborah Fisher, executive director of Tennessee Coalition for Open Government.

“…We need to be careful that any policy does not eliminate the accountability of police actions, no matter where they take place. Video of an officer who uses lethal force or excessive force inside someone’s home, for example, should not be protected, even if the state determines that the identity of the citizen in that situation should be,” Fisher said.

Richard Hollow, attorney for the Tennessee Press Association, emphasized to the committee the importance of transparency with public records, such as police records that hold government accountable. He noted that the Tennessee Supreme Court is currently considering a case that deals with how much police can keep confidential under current rules and how much they should release to the public.

State Sen. Brian Kelsey is the chairman of the state Judiciary Committee, which held the hearing.