A Davidson County chancellor took much-needed action last week.

She gave public accountability a boost and set the Attorney General’s Office straight on the Open Meetings Act.

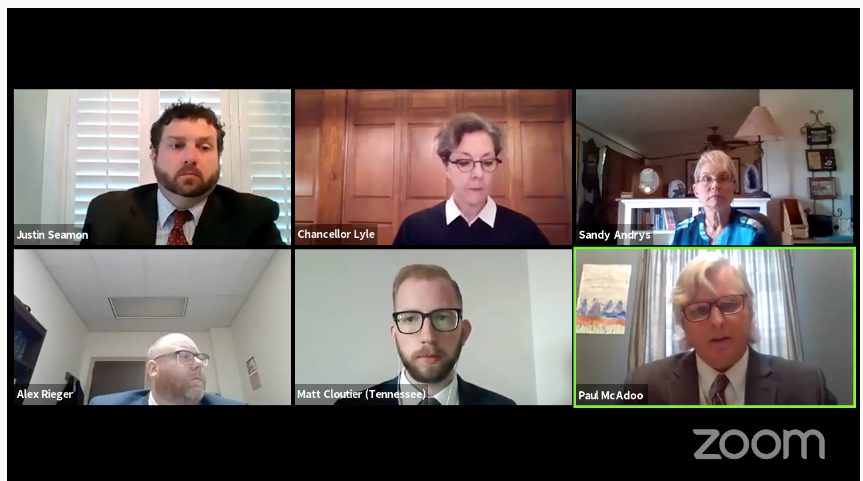

Chancellor Ellen Hobbs Lyle ruled on Friday that the Tennessee Registry of Election Finance violated the Open Meetings Act by holding an email vote — outside a public meeting and without public notice — to approve a settlement with a lawmaker, substantially reducing his outstanding fines.

The finance board did this with advice of the Attorney General’s Office.

So what happened here?

Earlier this year, the Attorney General’s Office advised the Registry’s executive director how to get a vote — without a public meeting or notice of a public meeting — from the six-member Tennessee Registry of Election Finance on whether to accept a settlement offer reducing fines against state Rep. Joe Towns, D-Memphis.

Towns, a perennial violator of the campaign finance disclosure laws for years, needed to pay his outstanding fines so that he could get on the ballot for reelection to his seat. The deadline was the next day and he wanted his $65,000 in fines reduced by more than two-thirds.

This is usually something the board considers in an open meeting. But Bill Young, the director for the Registry, said there wasn’t time, and he followed the Attorney General’s Office advice on how to ask board members individually to email their votes, which they did.

Later it came out that some board members did not appreciate such pressure. The Registry board’s longtime chairman, Tom Lawless, who voted no in the secret email vote, has said publicly that he thought the email vote violated the Open Meetings Act.

He was right, and a judge confirmed that on Friday.

Open meetings law requires votes be in public

The Open Meetings Act unambiguously requires that all votes by a governmental body be by public vote with no secret votes allowed. It requires that all decisions—and deliberations—by a governing body “on any matter” be done in a public meeting.

It also specifically prohibits the use of electronic communication to “decide or deliberate public business in circumvention of the spirit or requirements of” the Open Meetings Act.

So, first, the Attorney General’s Office gave advice that plainly is at odds with multiple parts of the statute.

But it didn’t stop there.

AG doubles down against transparency

The Attorney General’s Office had ample time to rethink its advice. Perhaps it was hasty, considering the pressure Towns had applied. The long-time lawmaker had threatened to challenge the constitutionality of the campaign finance disclosure laws if he didn’t get what he wanted.

Perhaps, in the morning light, or in the light of the weeks that followed, the Attorney General’s Office might have come to the conclusion that the public’s interest was best served by allowing transparency here and protecting the Open Meetings Act, not undermining it. After all, this was a government body making a decision about a public official.

This did not happen.

When news media organizations and the Tennessee Coalition for Open Government filed an open meetings lawsuit, outlining the clear violation, the Attorney General’s Office set its compass on creating a new loophole.

Instead of evaluating its own prior legal advice and acknowledging its mistake, it doubled down against government transparency.

AG argues for new loophole in Open Meetings Act

It argued that the court should adopt a brand new bright-line test on when a decision by a governing body must be in public by public vote and when it could be done in secret: Any decision that is inconsequential, that has no binding effect, could be secret.

In this case, the Attorney General’s Office argued, the Registry board technically had no authority to accept or reject the settlement offer made by the lawmaker. Once the Attorney General’s Office began representing the Registry board in trying to collect the outstanding fines, the Registry board gave up any such authority, according to the Attorney General.

This doesn’t square with what the Registry board has been doing for years — voting in public meetings on settlement offers brought to them by the Attorney General. And it doesn’t square with what the Registry board members appear to think is their legal duty. Nothing in the record indicates the Board members thought they were just recommending that the settlement be accepted.

Whether or not the Registry board is neutered once the Attorney General begins representing it is not the question here, though.

In the end, the board voted 4-2 by secret email, according to an announcement made afterward (the actual emails containing the votes have been withheld to this day). The public deserved to know why the board voted that certain way. The public deserved to have a chance to be in the meeting, hear the discussion about reducing a lawmaker’s fines by such a substantial amount and see the votes take place. That’s how accountability for members of governing bodies is supposed to work.

Judge finds Registry board’s decision should have been in public

Chancellor Lyle’s conclusion flatly rejected the Attorney General’s call for parsing the Open Meetings Act in such a way so that it would only apply for certain types of decisions made by a governing body.

Lyle said the Registry board members made a decision, and it was a weighty one in line with their responsibilities. She declared that the Registry board violated the Open Meetings Act.

The Registry may have been the governing body that violated the law, but the Attorney General’s Office is the entity that violated the public trust.

It’s not the first time. Another recent example was when NewsChannel 5’s Phil Williams in Nashville sought travel and spending records from two state agencies. The Attorney General’s office argued all the way to the Court of Appeals that the ordinary, garden-variety public records were exempt from the public records law because a district attorney was also reviewing them as part of a criminal investigation.

The Court of Appeals didn’t buy such nonsense.

AG should encourage compliance with open government laws

Tennessee citizens deserve a government whose top lawyers embrace its open government laws and encourage compliance instead of chasing loopholes that could render the laws powerless in providing public accountability.

The Attorney General’s Office, after all, is required by law to defend the constitutionality of these laws, a task one member of the Attorney General’s Office winced at in open court years ago when she told a federal judge that she really didn’t like the public records law though her job was to defend it.

The open meetings and public records laws in Tennessee will always have enemies who prefer that the people’s business be done away from public scrutiny.

We think it’s time that the Attorney General’s Office stop acting like one of them.