7-month quest for Gatlinburg fire records reflects poorly on state transparency

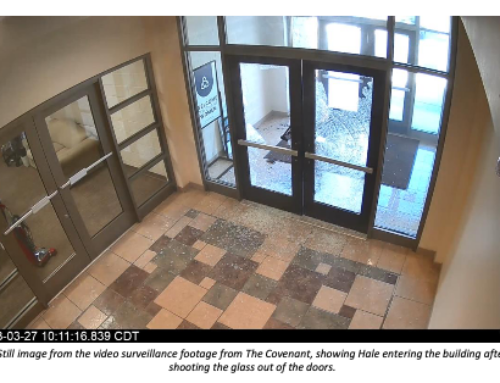

The November 2016 Gatlinburg fire killed 14 people and cost millions of dollars in damages.

It was one of Tennessee’s worst disasters.

A central question remains: Why did state and local officials wait so long to order an evacuation, until after the fire had already swept into residential areas?

Some who lived through last-minute escapes have told news reporters that they had called 911 and were instructed it was safe to stay put.

The answer to the evacuation question, and many others, could lay in the communication records and other post-fire reports held by state and local officials.

But almost as soon as news organizations and citizens started requesting to see those documents under the state’s public records laws, Jimmy Dunn, the district attorney for Sevier County, issued a letter instructing any government entity with records about the fire, including the response to the fire, not to release them.

This week, we learned just how rogue that letter was — and the state’s participation — through new court documents gained by the Knoxville News Sentinel.

Here is the sequence of events:

About one week after two juveniles were charged with aggravated arson for starting the fires high up in the mountains, Judge Jeff D. Rader who presides over juvenile court in Sevier County, issued a “gag order” to the defense attorneys and prosecutor Dunn. The Dec. 14 order read:

“Based upon the serious and unprecedented nature of this matter, the possibility of harm to the juvenile defendants and the nature of juvenile court generally, the Court hereby orders that any and all communication to the public regarding this case, including scheduling, shall originate from the Sevier County Juvenile Court.

“Counsel for the Defense and their agents, as well as the 4th District Attorney General’s Office and their agents, are prohibited from publicly disseminating information that is not a public record with media and the general public without specific permission of the Court.…”

Notable is that the judge makes clear in the order that public records can be disseminated to the public without permission from the court.

The judge’s order itself was not made public at the time, and only the parties of the case — and the state — would have been aware of its contents.

What did become public in December, and widely reported, was a letter issued the next day to media outlets by prosecutor Dunn. The letter stretched the judge’s non-disclosure instructions beyond recognition and proclaimed that all public records related to the government’s response to the fire were confidential and would not be disclosed.

“[A]ll state and local agencies involved in the response to and investigation of this fire and the resulting devastation are unable to respond to (public records) requests at this time,” Dunn wrote.

The leap from the judge’s order of not disseminating anything about the case except for public records to the district attorney’s order of not releasing any public records about the fire is stunning.

Dunn claimed that public knowledge of the contents of these records — records he didn’t specify nor apparently had even gathered or reviewed at the time — could harm his ongoing investigation into arson.

News organizations soon complained about not being able to get 911 calls, after-fire reports and assorted other public records they normally would review after a disaster — records that appeared unrelated to proving an arson case.

Questions about the local, state and national government’s response to the fire continued to build, and residents turned out at public meetings demanding answers.

Now, according to court records recently obtained by the Knoxville News Sentinel, we learned that during this time — in the background and outside of public view — the state was maneuvering to clarify and perhaps even make a case for keeping records confidential, despite the clear wording of the judge’s order.

The newly obtained documents reveal that Deputy State Attorney General Janet Kleinfelter petitioned the court on March 22 asking for clarification of Judge Rader’s order after a widower of a fire victim had requested Tennessee Emergency Management Agency communication records about its warnings to the public.

It is unclear why Kleinfelter used the widower’s public records request, when several other public records requests had also been made to TEMA by news media organizations, but she says in the petition that the widower had threatened legal action if the state did not respond.

While the court filing was titled “Petition to Authorize Disclosure of Records,” Kleinfelter included extensive arguments as to why such communication records might be confidential and why TEMA had not released the records thus far.

The judge, given the opportunity to modify his order, did not.

Instead, in a second order issued June 2 the judge reiterated that:

“This court did not intend to direct or address the actions of any other entities or parties not specifically involved in these cases. … TEMA has not been ordered to provide nor precluded from providing any information pertaining to its duties under the Public Records Act.”

TEMA says it is now working on accumulated public records requests. Local government entities are just now learning of the judge’s orders through the news media.

When will the records be released? Whatever happens, it may not be quick. And those wanting records may have to pay large fees.

Kleinfelter, in a letter to the widower’s attorney, described extensive staff time expected to produce the records and notified them that the state “will expect payment in advance of any production.”

One could speculate that TEMA might already have gathered and reviewed its communication records in the seven months after the fire. Or that these records about public warnings are of such public interest that they would be shared freely.

But so far, sharing information freely about the Gatlinburg wildfires appears to be a path the state is determined not to take.