What we learned from a citizen’s fight for public records in Sumner County

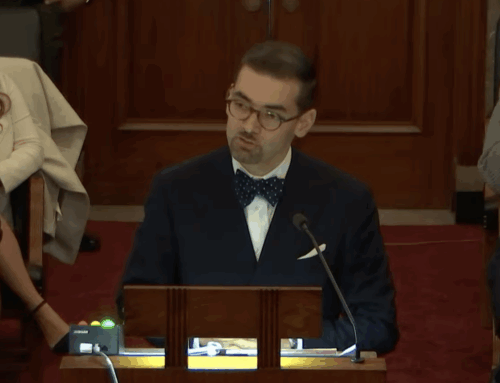

Judge Dee David Gay reads his ruling that the Sumner County Board of Education violated the Tennessee Public Records Act because it went too far in restricting how citizens could make requests. The school district would only allow citizens to view public records if they made their request in writing through the U.S. Postal Service or in person.

At a cost of about three or four college educations at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, Sumner County’s school officials and school board just got educated about the state’s public records law.

Sumner County parents and taxpayers paid the tuition.

On Nov. 13, Sumner County Judge Dee Gay ruled that the school district violated the Tennessee Public Records Act when it denied a citizen’s request to see a copy of its public records policy.

Ken Jakes waits for Judge Dee Gay’s ruling. In the background, Sumner Schools attorney Jim Fuqua talks with Jeremy Johnson, the school’s community relations officer who received Jakes’ public records request.

The school district had argued that it did not have to accept any request to see public records if the person made the request by email or by phone, which is what Joelton resident Ken Jakes did.

It took 20 months and a citizen who was willing to spend more than $10,000 of his own money on an attorney to tell the school district what should have been obvious all along. It can’t make up local rules to block access to public records. The judge ordered the school district to change its illegal public records policy to come into compliance with the law.

“It is a policy that is most convenient to the Defendant … without concern to the accessibility and convenience to the public,” Gay wrote. “Further, when the individual options (for making a request) are analyzed under the law individually, they present options that are not favored by statute or case law.”

The judge, who had chided the school district for its “Pony Express” attitude, recommended that the new policy “be expanded to accommodate the methods of modern communication.”

In 2008, the Tennessee Legislature improved the public records law to get rid of some of the nonsense that was needlessly blocking access to government records and frustrating citizens who were trying to know what their government was doing.

First, lawmakers added language that public records should be provided “promptly” when a citizen asks. But if that isn’t possible — such as if the request is for a large number of documents or a question exists about confidentiality — lawmakers said a government entity could take seven business days to get back with the requester. Even then, a government entity could simply tell the requester how much longer it would take to compile the records.

There are more than 350 exemptions to the Tennessee Public Records Act. But the record requested by Jakes — a one-page school board records policy — was not exempt and the request was not large.

In fact, the policy was available online if you knew where to look. As the judge noted, the schools’ community relations officer could have simply emailed back a link.

An office that was designed to help

Another step the Legislature took in 2008 was to establish the Office of Open Records Counsel. Many states have similar entities, often called an ombudsman, with varying degrees of authority. The idea behind these offices is to help citizens gain access to public documents when they are having difficulty and provide guidance on the law to government entities so they can comply. They provide best practices for government, and they are usually a way to settle disputes and misunderstandings before a costly lawsuit is sought. In some states (not in Tennessee), a judge can levy civil or criminal penalties against a governmental entity found to violate the law.

(See law creating the Tennessee Office of Open Records Counsel here.)

The trial in July raised questions about the effectiveness of the law changes in 2008.

For example, the school district’s community relations official Jeremy Johnson testified that he often provided public records to journalists who emailed and asked for them. But if someone mentioned the Tennessee Public Records Act in their email request, he told them they had to mail a written request through the U.S. Postal Service or appear in person in Gallatin before he would respond.

This is just plain bizarre. Whatever Johnson’s reasoning, surely it was not the intent of the Legislature that mentioning the Tennessee Public Records Act would actually make it harder and take longer to see a readily available, non-exempt public record. And more specifically, that the word “promptly” added to the law in 2008 could be so easily undermined.

Another question was the effectiveness of the Office of Open Records Counsel.

In the Sumner County ruling, the judge quoted heavily from state law, but also from the Best Practices Guidelines on the Open Records Counsel’s website.

“From the (Tennessee Public Records Act) and the (Best Practices Guidelines), it is very clear to this Court that in the application of the TPRA that openness and accessibility of non-exempt records are favored. It is also very clear that the law has placed no restriction on the form or the format of a request for inspection of public records other than: (1) a request for inspection or viewing cannot be required to be initiated by a written request; (2) any request for inspection of a public records shall be sufficiently detailed to enable the record custodian to identify the records,” Gay said in his order.

The school board’s attorney, Jim Fuqua, testified that after a 45-minute phone conversation with then-Open Records Counsel Elisha Hodge, he thought the school district was on solid ground to refuse a request that came by email.

Did Hodge, an expert in public records law, give Fuqua the clearance to reject Jakes’ request despite state law, at least two relevant appellate court decisions and Best Practices Guidelines that seemed to shout the opposite on her own website?

Best Practices Guideline Number 3: “A records custodian should make requested records available as promptly as possible in accordance with T.C.A. 10-7-503.”

Best Practices Guideline Number 5: “To the extent possible, when records are maintained electronically, records custodians should produce records requests electronically. Records should be produced electronically whenever feasible as a means of utilizing the most “economical and efficient method of producing records.”

From Court of Appeals in Waller v. Bryan: “If the citizen requesting inspection and copying the documents can sufficiently identify those documents so that the appellees know which documents to copy, a requirement that a person must appear in person to request a copy of those documents would place form over substance and not be consistent with the clear intent of the Legislature.”

We don’t know because Hodge was not called to testify. Nor did she provide a written advisory opinion on the topic, which Fuqua could have requested after his conversation with her. By law, an advisory opinion would be posted as a public record on the Open Records Counsel website.

But the bigger question is whether the Legislature’s intent in creating the Office of Open Records Counsel was carried out in this situation. Was the Open Records Counsel able to, as the law instructs, “assist with the resolution of issues concerning the open records law” in a way that could have helped a Sumner County school district avoid huge legal bills? If not, why not?

I don’t know the answer. But considering the expense and angst of this case, it might be worth asking the question. Was this an issue that truly needed to go to court?

(Sumner Schools’ underlying argument — and unbelievable testimony — was that taking email or phone calls from the public is dangerous, risky and expensive.)

What we do know is that the school district spent about $83,000 through February on outside attorneys to try to prove this and other thin excuses, and still hasn’t gotten billed for nine months of work, including work during the trial. Jakes said he has spent more than $10,000 on his attorney. The court and court staff have spent several days on it, and school officials have spent many paid work hours related to the defense. The cost has been enormous.

Takeaways from the judge’s ruling

Read Judge Gay’s ruling here: Judge Dee David Gay ruling in Jakes vs Sumner County Board of Education

Most important, the justice system worked. Judge Gay considered the facts of the situation and applied the law. The independence of the judiciary is an important feature of our government and those who think you can’t get a fair shake by a local judge in a public records case against a local government entity where connections are thick were wrong. Judge Gay upheld the law in regard to the school district’s illegal public records practices and took what may be an unpopular action against people he probably knows in favor of someone he doesn’t from another county.

“The School Board’s Policies allow two forced “choices/elections” that contravene or are inconsistent with the policy of the Open Records Act which requires the TPRA to be ‘broadly construed so as to give the fullest possible access to public records,’ T.C.A. 10-7-505(d) and the present case law. The policies are only for the convenience of the Defendant – an entity which processes only twelve to fifteen requests for public records each year. Therefore, this Court finds that the policies of the Defendant for accepting requests for public records for inspection by writing or in person, and the new policy specifically prohibiting all other forms for requests for inspections, are in violation of the TPRA.”

Gay’s order only applies to Sumner County, but it’s a message I hope will be heard across the state. I’ve already seen one other school board policy in Middle Tennessee which bans public records requests by email. They should get rid of it. Gay relied on the statute, but also established case law in Waller v. Bryan and Allen v. Day , and this year, Friedmann v. Marshall County, Tennessee.

As executive director of a nonprofit organization that promotes open government through better education, I would have liked to have seen Jakes compensated for his attorneys fees. Not because the taxpayers of Sumner County deserve to lose any more on this case than they already have. But because, in Tennessee, it is so hard to enforce the law. The citizen has to do it through a lawsuit, and government officials, whether right or wrong, can use seemingly unlimited taxpayer money to fight it. The changes put in place in 2008 to improve compliance through other means did not work in this case.

We should not stop investing in safeguards to protect open government. But in the end, Kenneth L. Jakes vs. Sumner County Board of Education demonstrates how citizens must be the ultimate watchdog.