Washington Post story details Google techniques to keep economic development deals secret

A Washington Post story last week has detailed how Google, often acting through a newly formed company with a different name, secured non-disclosure agreements with government entities around the country as it negotiated and landed economic development deals valued in the millions of dollars.

The city of Clarksville and the Montgomery County Industrial Development Board are among the government entities that signed non-disclosure agreements with Google, which eventually agreed to locate a data center in the county with a target investment of $600 million and 34 direct hires.

The city of Clarksville and the Montgomery County Industrial Development Board are among the government entities that signed non-disclosure agreements with Google, which eventually agreed to locate a data center in the county with a target investment of $600 million and 34 direct hires.

From the Washington Post story, Google reaped millions in tax breaks as it secretly expanded its real estate footprint across the U.S.:

Google — which has risen to become one of the world’s most valuable companies by transforming the public’s ability to access information — has vastly expanded its geographic footprint over the past decade, building more than 15 data centers on three continents and 70 offices worldwide. But that development spree has often been shrouded in secrecy, making it nearly impossible for some communities to know, let alone protest or debate, who is using their land, their resources and their tax dollars until after the fact, according to Washington Post interviews and newly released public records obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request.

In Clarksville, for example, the city signed a non-disclosure in which the company prohibited the city from disclosing information the company deemed as “confidential information” and acknowledging only that any “definitive agreement” between Google and the city would be public record if it “were to be executed.”

The agreement also required the city to “promptly notify Google upon receipt of any public/open records law request for any Confidential Information.”

Further, the Clarksville agreement required the city to contest disclosures and allow Google to “assume control” over the city’s actions and decisions:

“The City shall contest disclosure or release of Google’s Confidential Information and cooperate with Google in contesting disclosure or release of Google’s Confidential Information. To the extent allowed by applicable law, Google may assume control of the actions to be taken and decisions to be made with respect to contesting the disclosure or release of Google’s Confidential Information, including using counsel selected and paid for by Google.”

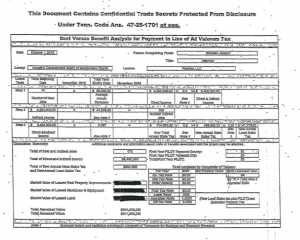

The Montgomery County Industrial Development Board also signed a non-disclosure agreement with Google (working through a newly set-up company, Foxman LLC) that included not allowing the government entity to attach a copy of the Payment In Lieu of Tax Agreement “to any public notice or present this Agreement for review in any public forum or provide a copy or disclose the terms or conditions of this Agreement to any third party…”

The PILOT agreement lays out the terms in which the industrial development board would allow Google to locate on and use government-owned property without paying millions of dollars in property taxes, as well as assistance the board will provide in financing for improvements.

Limiting information until after a vote could conflict with Tennessee law

In both instances, the city and industrial development board agreements had the effect in 2015 of not allowing the public to have key information about the deals until after a vote by the local governing bodies. The IDB executive director would not reveal any information and would only say they were working with an undisclosed prospect under the “tightest non-disclosure agreement that I can remember in my 18 years in this position.”

Until the law changed in 2017, all government records at the local level related to economic development were subject to the Public Records Act, though agencies sometimes withheld them anyway and often worked hard to keep secret that a deal was under negotiation so that no one would ask.

In 2017, the law was updated to allow cities and counties to negotiate in confidence while details of an agreement were being worked out, but the law made clear that all records must be “open for public inspection as of the date such contract or agreement is made available to members of the governing body.” (See T.C.A. § 6-54-142 and T.C.A. § 5-1-130).

The 2017 change also included a provision that requires city and county governing bodies to “publicly disclose the proposed contract or agreement in a manner that would adequately notify and fairly inform the public of the proposed contract or agreement before voting on the proposal.”

Since then, Memphis officials have asked if they can hide the identity of companies until after the vote and still comply with the new law.

Keeping residents in the dark

The Washington Post story outlined an example near Dallas in which the public was kept in the dark until after a vote:

Last May, officials in Midlothian, Tex., a city near Dallas, approved more than $10 million in tax breaks for a huge, mysterious new development across from a shuttered Toys R Us warehouse.

That day was the first time officials had spoken publicly about an enigmatic developer’s plans to build a sprawling data center. The developer, which incorporated with the state four months earlier, went by the name Sharka LLC. City officials declined at the time to say who was behind Sharka.

The mystery company was Google — a fact the city revealed two months later, after the project was formally approved. Larry Barnett, president of Midlothian Economic Development, one of the agencies that negotiated the data center deal, said he knew at the time the tech giant was the one seeking a decade of tax giveaways for the project, but he was prohibited from disclosing it because the company had demanded secrecy.

“I’m confident that had the community known this project was under the direction of Google, people would have spoken out, but we were never given the chance to speak,” said Travis Smith, managing editor of the Waxahachie Daily Light, the local paper. “We didn’t know that it was Google until after it passed.”

Cities and counties risk being sued by Google over disclosures

The story also highlights the position of cities and counties, who sign such agreements as they are trying to land a job-creating deal and then risk a lawsuit from the company if they share any information about their actions or the eventual proposal that the company might deem as “confidential business information.”

Midlothian’s Barnett said it was written so broadly that he feared even disclosing the existence of an agreement would violate the NDA, echoing similar statements from officials in other locations.

Smaller cities, in particular, face a sizable power imbalance when they go to negotiate with some of the wealthiest companies in the world, (Stanford Law Professor Michelle) Wilde Anderson added. Some are so cash-strapped that they lack a single full-time lawyer, she said. Breaking the rules could mean getting into a costly lawsuit with an adversary with a seemingly endless budget.

“Google’s huge and well-resourced legal team pushes an NDA across the table, and it’s just a mismatch of resources,” she said. “Like many parts of life, you get what you pay for.”

In Midlothian, Google’s subsidiary had the authority to determine which documents would be disclosed, even if the state attorney general said they were subject to transparency law, according to the records.

Google continues to claim the market value of government land it received is confidential

In Tennessee, Google has continued to claim that the market value of the leased land, property improvements and machinery and equipment that the Montgomery County IDB has given Google to use is confidential.

In Tennessee, Google has continued to claim that the market value of the leased land, property improvements and machinery and equipment that the Montgomery County IDB has given Google to use is confidential.

Although these details are documented on a cost-benefit analysis document required by the state, and have ordinarily been released in other PILOT deals, Google forced the Montgomery County Industrial Development Board to redact those monetary values when the document has been requested under the public record law.