TN Democratic Party’s public records suit over absentee ballots misfires

Davidson County Chancellor Patricia Moskal denied a request for an injunction to force the production of data that could show which Tennesseans have not yet returned absentee ballots. Her ruling was based largely on lack of proof that a public records request for the data had actually been made.

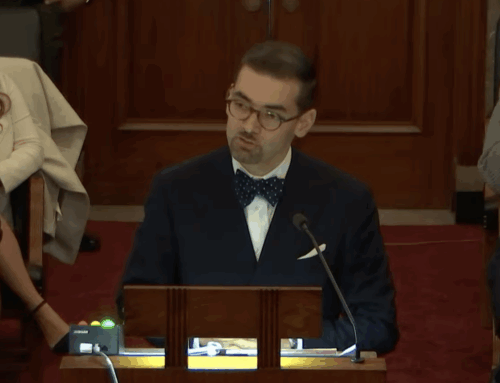

In an election eve hearing today, attorney Benjamin Gastel of Branstetter, Stranch & Jennings, argued that his client, the Tennessee Democratic Party, and the other plaintiff, the Marquita Bradshaw for Senate Campaign, had requested the data from five county election commissions and the Secretary of State’s office.

Gastel said they wanted to find out the names of the people who had requested absentee ballots, but not yet returned them, so they could contact them and let them know how to do that. By now, if someone hasn’t returned an absentee ballot, the only sure way to get it counted on Election Day is to drop it off at the one post office in their county designated for that purpose.

However, when questioned by the chancellor, Gastel did not know to whom the public records requests had been made at the Secretary of State’s office, whose officials were the only named defendants in the lawsuit. (The county election commissions were not named as defendants.) He said the request to the state was by phone. No copy of the request had been filed with the request for injunction.

“There is insufficient proof in the record that the Bradshaw campaign complied with the requirements of the TPRA (Tennessee Public Records Act) and made a public records request to either named Defendant,” Moskal wrote.

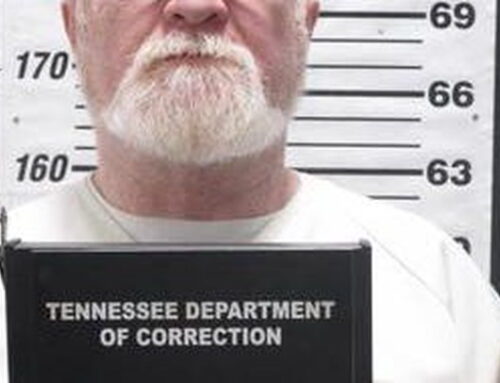

The complaint was filed against Mark Goins, the state’s coordinator of elections, and Tre Hargett, Secretary of State.

State says it would take 24 hours to extract data that Democrats wanted

The state, represented by Deputy Attorney General Janet Kleinfelter, acknowledged that if a public records request had been made to the Division of Elections — even as late as Friday, the state could have written a program to extract the data being requested. She said it would take about 24 hours to write the program and extract the data.

But she told Moskal that the Secretary of State’s office never received a request for the information, either by phone or a written request.

“You cannot deny a request that was never received,” she said.

The state also produced a declaration of Mary Beth Thomas, the counsel and public records coordinator for the Department of State, that said she had not as of Sunday, Nov. 1, received a request from the Tennessee Democratic Party or from Marquita Bradshaw for U.S. Senate “for records or information relating to absentee voters who have requested but not yet returned a ballot.”

Moskal said in her order that “[t]o the extent the requested public record information is readily available, it is the statutory duty and responsibility under the TPRA, of those in lawful possession of those public records to provide the information promptly upon request.

“While this factor weighs heavily in favor of the requested injunctive relief, it does not overcome the statutory requirements imposed for making a proper public records request to the appropriate records custodian.”

The Democratic Party and Bradshaw’s campaign had alleged in their complaint that the Secretary of State’s office had told county election officials that they did not have to comply with requests made at the local level.

Knox County election commission provided list when requested

Though the lawsuit was against the state, the Democratic party and Bradshaw’s campaign said they had also made requests to election commissions in five counties — Knox County, Shelby County, Davidson County, Madison County and Washington County.

Only Knox County, according to the plaintiffs, gave them the data. And they gave it within about 45 minutes.

Gastel argued that the state had the information also and it could be supplied promptly, pointing to the quick turnaround in Knox County.

Kleinfelter argued that Knox County had access to an IT professional from the county, something not all the other counties had.

Gastel insisted that the plaintiffs had called the secretary of state asking for the information, and they were denied. He also said he included the request in an email on Sunday.

“They have it, they just don’t want to produce it,” he said.

For her part, Kleinfelter confirmed that the information is in the state’s possession and is electronically stored. But she argued that at this late date, it would be wrong to order the state to stop its preparations for the elections and produce it.

She said the information is not something that is routinely produced.

See the order, the plaintiff’s complaint and the state’s response to the complaint.

The hearing was held via Zoom on Monday morning.