Times Free Press: AG’s opinion gives Erlanger another bonus dilemma

Following is a reprint of today’s Chattanooga Times Free Press story about the AG’s opinion on requirements for public hospital boards under the Tennessee Open Meetings Act. The Times Free Press graciously gave TCOG permission to reprint the article:

By Kate Belz

The status of $1.7 million in bonuses paid out to Erlanger Health System’s management has again been called into question, as a new opinion issued by the state’s attorney general has local lawmakers calling for the money to be paid back.

Attorney General Herbert H. Slatery III’s opinion, issued Wednesday, states that Tennessee law does not permit hospitals such as Erlanger to meet in a closed session to discuss bonuses or salaries.

While the opinion does not specifically reference Erlanger, Rep. Mike Carter, R-Ooltewah, said it proves Erlanger’s public hospital board “clearly violated the law” in the process it used to approve executive bonuses for year-end performance — half of which of have already been paid out.

On Thursday, hospital officials did not disclose specific steps — if any — they would take in response to the AG opinion. But in a statement they struck a conciliatory tone, saying Erlanger “fully appreciates the legislative delegation’s involvement to help us obtain clarification” of open meetings law.

“Certainly, the more guidance we can get, particularly with more than 200 exemptions to the Act, the more prepared public hospitals like Erlanger will be in ensuring compliance under the [Open Meetings Act],” the statement said.

“Erlanger will continue to review and, if necessary, adjust our processes in order to avoid any appearance of noncompliance and govern itself in full accordance with applicable laws. Similarly, we fully intend to continue our work with the legislative delegation going forward. As always, Erlanger’s intention has been to comply with this act and we will continue to do so.”

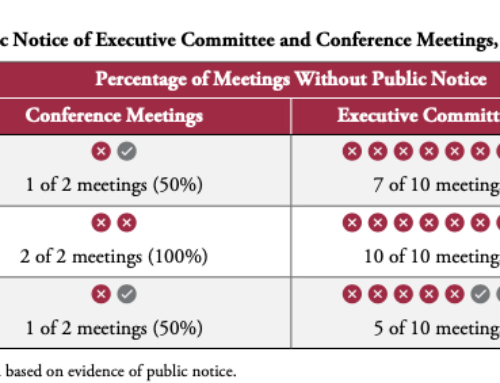

The opinion was triggered by local lawmakers’ concerns about how the hospital board went about its decision at a Dec. 4 meeting to award the bonuses. The decision riled lawmakers, as well as rank-and-file hospital employees who had endured a series of major cuts to their own benefits as the hospital sought to recover financially.

The resolution concerning the bonuses was added to the agenda just hours before the public meeting; and besides outlining what the compensation entailed, trustees did not engage in any public discussion or debate about the bonuses before voting. All but one trustee voted to approve the resolution.

While the apparent abruptness of the decision sparked outrage, trustees said the performance goals had been made months earlier and the bonuses had been vetted in earlier closed committees.

But that, lawmakers said, was the problem.

The Open Meetings Act, which Erlanger is beholden to as a public hospital, requires public officials to conduct all their deliberations in public. A state law passed in 2008 gives public hospitals an exception in order to “develop marketing strategies and strategic plans” so they can compete with private hospitals.

Erlanger often relies on that law to close committee meetings hospital representatives say are sensitive to competition.

After the fallout, trustees initially responded by freezing the bonuses, saying they would seek their own legal opinion as to whether they violated open meetings law. The board’s hired law firm — Spears, Moore, Rebman and Williams — said trustees did not violate open meeting laws and that “no deliberations took place” regarding the incentive plan.

At that point, lawmakers said an outside opinion was needed. In his opinion, Slatery wrote that the law “would not permit the board of a public hospital to meet in closed session to discuss executive compensation.”

Slatery also wrote that based on the language of the 2008 law, “it is apparent that the legislature intended the confidentiality provisions of [the law] to apply to a public hospital’s discussion and development of its long-term plans for promoting the products and services of the hospital and not the determination of executive compensation and executive bonuses.”

Furthermore, Slatery said any studies used in the meetings must be available to the public for at least seven days before any vote.

Sen. Todd Gardenhire, R-Chattanooga, said the AG’s opinion left him “relieved that we have an official, truly non-partisan opinion that showed the Erlanger board was wrong,” and also “saddened, because it means decisions need to be made about how to pay the penalty and fix the problem.”

He and Carter already responded to the controversy by introducing HB16/SB26, which would remove the 2008 Open Meetings loophole for every public hospital in the state.

“I’m going to push forward with it,” Carter said. “I have chastised the hospital boards and the state hospital association for not policing their own members about what they can’t do in these meetings.”

Deborah Fisher, executive director of the Tennessee Coalition for Open Government, said the problem is not in the current law, but rather how the hospital apparently interpreted it.

“It’s not a complicated law,” she said. “It’s frustrating to people when a governing board tries to interpret the law in a way that it clearly is not written. I am glad the AG issued an opinion on it.”

What is less clear is how the hospital should proceed. The hospital has already paid out half of the bonuses, with the second installment to be paid in July.

Legally, the AG’s opinion itself does not make the board’s vote on the bonuses null and void, Fisher said. There are two things that could now happen, she said.

First, the hospital board could take a proactive approach and try to remedy its procedure with a do-over of sorts.

“They could have another meeting, put the item on the agenda, invite the public and have anyone who wants to ask questions weigh in,” Fisher said. “Then could engage in substantial reconsideration of that decision in public — not just rubber-stamping their previous decision — before voting. That would be the best thing to do.”

That may involve having the hospital recoup the bonuses first, something lawmakers insist on.

“I’m sure those people earned it, and may have already spent it, but they need to do the right thing,” Gardenhire said.

The alternative, Fisher said, would likely be a lawsuit. If a judge ruled against the hospital, all action taken during the meeting would be void.

Both Gardenhire and Carter said they would be willing to spearhead a lawsuit if the hospital insists it is in the right.

“Everyone would respect [the board] if they attempted to fix it,” Fisher said, “instead of trying to fight some long battle.”

Contact staff writer Kate Belz at [email protected] or 423-757-6673.