State should address secretive culture around lethal injection drugs

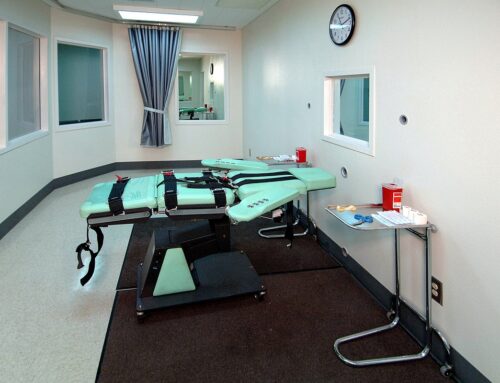

In 2015, the state legislature at the urging of the Department of Correction passed a law allowing it to keep secret the companies that make and sell lethal injection drugs to the Tennessee Department of Correction for death penalty executions.

This week, the public is getting a glimpse of how that secrecy has worked out.

An investigative review released by Gov. Bill Lee has revealed a number of missteps, sloppiness and failures by prison leadership and staff and the individuals and companies with which they worked to carry out executions.

Importantly, the investigation exposed that the department of correction for years has not followed its own protocols for testing the lethal injection drugs it received from a non-traditional pharmacy to ensure they were not defective.

Of the seven executions carried out since a new protocol was established in 2018, only once were any of the lethal injection chemicals tested for endotoxins as required by the protocol, the investigation showed. Testing for endotoxins ensures that injection drugs have not been contaminated and will work as intended.

This is significant because questions about defective lethal injection chemicals have been an ongoing concern, particularly as states have turned to secret compounding pharmacies to get the drugs and as one of the drugs that is supposed to sedate the inmate, midazolam, has become suspected in botched executions around the country.

‘Not one’ employee ensured compliance with execution drug protocols

Former U.S. Attorney Edward L. Stanton III led the independent investigation into Tennessee’s use of lethal injection drugs.

“The fact of the matter is not one TDOC employee made it their duty to understand the current Protocol’s testing requirements and ensure compliance with the same,” said the report.

The lack of rigor in ensuring compliance with protocols is the opposite of how the state has characterized itself in court when lawyers for death row inmates have pressed to get more information about the lethal injection drugs. “Trust us” has been the state’s theme.

As it turns out, the responsibility for the lethal injection chemicals fell on a single department of correction employee who had no medical or pharmaceutical background but was charged with finding and buying them. This person, who state law allows to be anonymous, was the point person in communication between the pharmacy and its pharmacist and was the sole person who received and reviewed the testing results. The report says the employee had little, if any, professional guidance, resources or assistance.

How could this be? The investigation, led by former U.S. Attorney Edward L. Stanton III with Butler Snow law firm, found that the state simply had a focus different from the integrity of the execution itself.

“TDOC leadership viewed the lethal injection process through a tunnel-vision, result-oriented lens rather than provide TDOC with the necessary guidance and counsel needed to ensure that Tennessee’s lethal injection protocol was thorough, consistent, and followed,” the report said.

Gov. Bill Lee promises new leadership, changes to execution process

The governor has promised to make staffing changes at the department’s leadership level, revise the state’s lethal injection protocols and make updates to operations and training.

But it should not go unnoticed how the lack of transparency in the state’s execution process has for too many years contributed to a lack of accountability.

Nobody inside the department of correction, or the attorney general’s office for that matter, seemed to be asking the right questions — or perhaps they were asking no questions. But questions were being asked from the outside.

In fact, it was federal public defender Kelley Henry’s request in April for a copy of test results of the drugs for the upcoming execution of her client Oscar Smith that triggered the governor’s call for an independent investigation.

The report released this week describes Henry’s request setting off a scramble within TDOC to determine whether the testing results existed, and, upon the realization that the testing protocol had not been followed, asking the pharmacist whether testing could still be completed in the hours before the execution was scheduled.

Eventually, the governor called off the execution, giving Smith a temporary reprieve.

State denied 2019 public records request for data on lethal injection drugs

This was not the first time Henry had asked for information concerning the execution drugs. In May 2019, Henry made an unsuccessful public records request for “all data regarding the lethal injection chemicals” used in the execution of her client Donnie Johnson. The state gave some information, but did not provide lab reports, noting the confidentiality statute passed in 2015.

Henry said she finally in the spring of 2022 saw lab records for execution drugs that she had sought in Johnson’s case in 2019. They had been provided by the state in another case. The lack of endotoxin tests affirmed her suspicion that the state was not following the processes to make sure the drugs were not defective.

It’s unclear to me how the state’s lawyers, who helped create the protocols, did not also realize that the protocols had not been followed, having surely reviewed testing records in response to Henry’s 2019 public records request before denying access, then eventually providing records in another case.

Regardless of the state’s understanding of its own responsibility, just weeks after Henry saw the lab test results on the 2019 execution drugs, she sent a new request for test results for the upcoming 2022 execution.

The governor, when the information about ignored protocols finally reached him, was alarmed. In ordering an independent investigation, he said that while he believes the death penalty “is an appropriate punishment for heinous crimes,” executions are “an extremely serious matter, and I expect the Tennessee Department of Correction to leave no question that procedures are correctly followed.”

Reluctance to share information allowed prison officials to avoid accountability

The investigative report is damning, particularly in revealing the lack of internal checks to ensure all protocols are followed. Other gaps were found, such as being prepared to use chemicals before receiving results from all the required tests.

The two correction commissioners who have presided over executions — Tony Parker and Lisa Helton — both indicated that a more rigorous review system would ensure accountability. However, the report said that “(s)everal individuals referenced TDOC’s general preference to have limited documentation…”

While the scope of the report does not explore the state’s excessively defensive posture and reluctance to share information, this secretiveness should be addressed going forward.

The disturbing problems uncovered by the investigation could have been addressed years ago if access to government records had been allowed and the state had embraced transparency instead of hunkering down to conceal what turned out to be flawed processes.