If you ever wondered about the importance of access to public records, watch the movie Spotlight

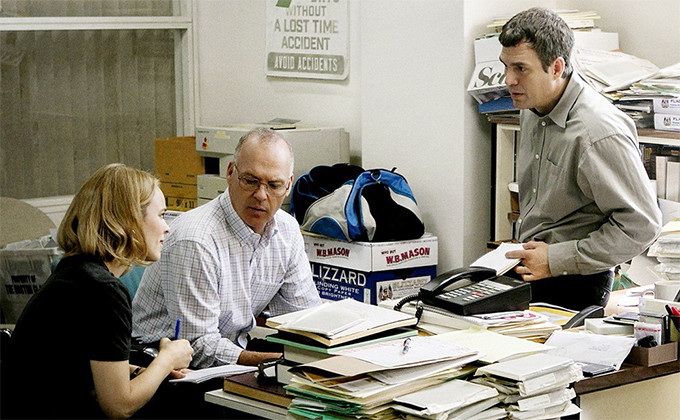

Scene from the movie Spotlight, which portrays the investigative reporting team of The Boston Globe who used public documents to help uncover a story of abuse of children by priests.

There’s a great scene about public records in the movie Spotlight, which is based on the true story of The Boston Globe’s investigative reporting of child sex abuse by Catholic priests.

Reporter Michael Rezendes rushes to the court clerk’s office to get an exhibit that had been filed as part of a court motion. It contained letters and evidence that showed that the Archdiocese of Boston had known about the molestation of children for years, but failed to stop it.

The reporter gets to the Suffolk County Recorder’s office just as they are closing, and the clerk would not help him. But he is there again when the doors open in the morning and asks for the records.

“Those records are sealed,” says the clerk.

“No, that’s a public motion. Those records are public. I work for the Globe,” Rezendes replies.

“Good for you,” the clerk says, unmoved.

“Can I talk with your supervisor?” the reporter asks.

“Not in today,” the clerk responds.

Rezendes then goes to the judge’s office.

“These exhibits you are after, Mr. Rezendes, they are very sensitive records,” the judge says.

“With all due respect, your honor, that’s not the question. The records are public,” the reporter says.

“Maybe so. But tell me, where is the editorial responsibility in publishing records of this nature?” the judge asks.

The reporter replies with a line that beautifully captures a conviction about the role of the First Amendment in our society.

“Where is the editorial responsibility in not publishing them?”

The reporter gets the records and they become the basis for a report that helped crack open one of the more stomach-turning stories of our time — a trusted institution that failed its own values and people, hurt children and hid it.

There’s more intrigue in the movie surrounding the pursuit of the records — including official documents that went missing from a court file, and a judge described as “a good Catholic girl” who hands the newspaper a First Amendment victory in court.

The story is relevant because it displays the tension that occurs when access to public records is blocked in the name of some sort of “other good.” Here, the “other good” was protection of the church, and many lined up to keep things secret. But in this case, that secrecy lay squarely in opposition to the fundamental principle that the public has an interest in the functioning of its justice system. Judges recognized that and the Boston Globe was able to get the story.

Few struggles to gain access to public records are dramatic enough for a movie. But after 25 years in newsrooms as a reporter and editor, I can easily say that statutory and constitutional access to government records and court records are critical in maintaining a free and independent press. They are critical in the ability of citizens to get at the truth and facts of how their government is operating — from the local county government to the largest institutions that serve our democracy.

A fresh debate capturing some of the same tension and discomfort with media scrutiny as in the movie Spotlight is being played out right now across the country.

Against the backdrop of high-profile officer-involved shootings, many police and sheriff’s departments are spending millions of dollars to outfit their officers with body cameras, creating thousands of hours of video footage of interaction between police and citizens.

Many people believe that the video — a public record — will increase law enforcement accountability.

But in Memphis, the mayor has said footage will be kept confidential if it’s related to an ongoing investigation. In fact, he said in a TV interview, it must be kept confidential.

Play that out. If an officer uses lethal force, and an investigation is launched, any video that captured events leading up to the event, or the event itself, will be kept from the public for months, maybe years in some situations as investigations drag on and cases work their way through the system.

Seeing such difficult footage may raise questions, at times, of citizen privacy and fair trials. But it also pits those issues squarely against the very First Amendment rights that allowed the Boston Globe to finally bring sunlight onto the Catholic Church’s coverup.

A handful of competing bills in the Tennessee Legislature seek to navigate the body camera issue. Some appear to be headed to restrict the press — or for that matter, the public — from seeing relevant records created by police cameras, essentially sealing some or all of them in advance. The Tennessee Supreme Court is weighing arguments in a case that deals with similar constitutional issues, which might be a reason to slow down.

Should Tennesseans care about access to public records?

In the movie, the editor of the Boston Globe, Marty Baron, is warned that trying to get access to certain court records will be viewed as an attack against the church. His publisher notes that 53 percent of the newspaper’s subscriber base is Catholic.

“I think they will be interested,” Baron replies.

As it turned out in Boston, sunlight proved itself again as the best disinfectant.