Settlement requires Memphis Shelby Crime Commission to produce records

The Memphis Shelby Crime Commission has released records about its funding of the Memphis Police Department a year after a public records lawsuit.

Wendi Thomas, founder of MLK50: Justice Through Journalism, and The Marshall Project argued that the crime commission was the “functional equivalent” of government because of its significant role in funding police and directing public safety policy in Memphis.

Under Tennessee’s “functional equivalent doctrine,” a government entity cannot avoid disclosure under the state’s Public Records Act by delegating its responsibilities to a private entity.

Tennessee courts have used the “functional equivalent” test to rule that certain private entities are subject to the public records law.

Journalists argued functional equivalent doctrine applied

The crime commission is organized as a private nonprofit. The lawsuit pointed out several factors, however, that indicated it was operating as a functional equivalent of government. For example, it provides extensive funding of government operations. Also, its board includes many public officials, including city and county mayors, the Memphis police director and the district attorney.

The parties reached a settlement in the case, agreeing to the release of records. Chancellor JoeDae L. Jenkins approved the settlement on Feb. 6.

Lawsuit sought to shed light on how commission direct public policy

The settlement required the crime commission to release records sought by Thomas in November 2018. Thomas said she is attempting to shed light on how the crime commission creates and directs local public policy. The records include sources of the commission’s funding as well as reports, contracts and emails.

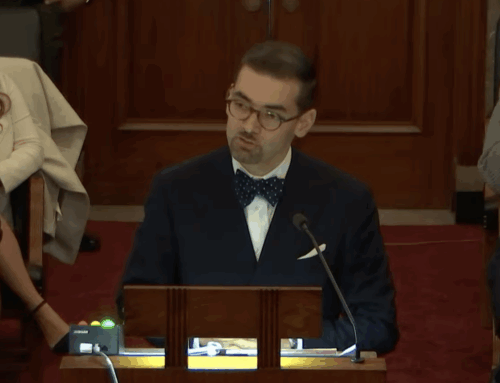

“Before this case, the Crime Commission was accountable to no one beyond their own closed doors and the big donors who they insisted on keeping anonymous,” said Lucian T. Pera, partner at Adams and Reese LLP. “Because of my clients’ persistence, Memphians now know more about the Crime Commission and its donors than we ever would have otherwise.”

The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press assisted in the case.

The settlement also requires the commission to make public agendas for board meetings 48 hours in advance. It must also provide the public minutes of its meetings.