Other states outpace Tennessee in COVID-19 data provided to citizens

Several other states are releasing more information to its citizens than Tennessee about the rapidly spreading COVID-19 virus.

For example, several states are releasing on their websites deaths by COVID-19 by county, and others are announcing the city or county location of deaths in press briefings.

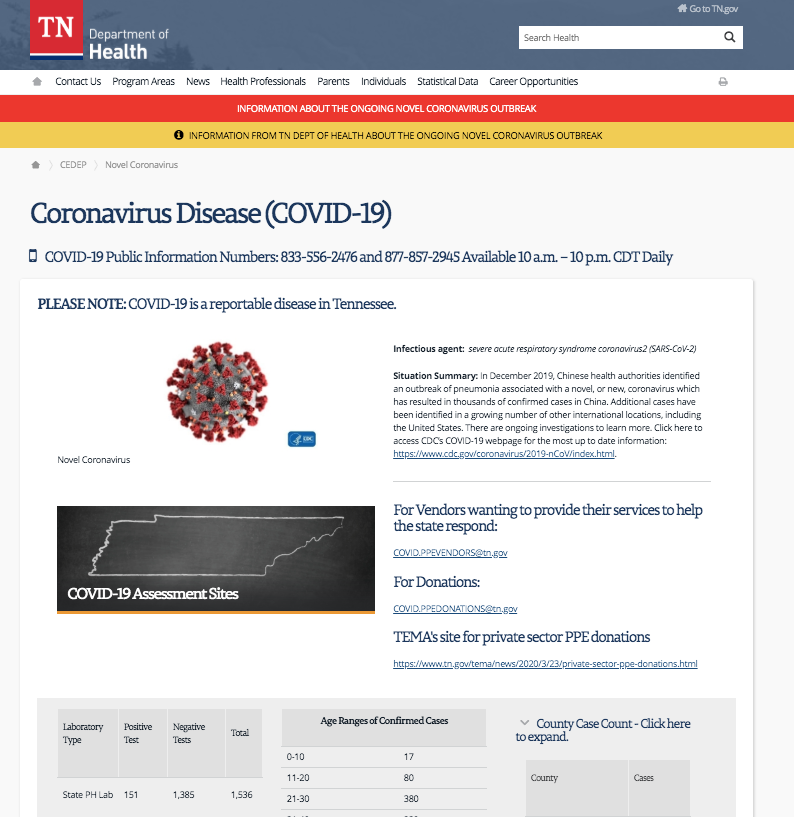

In contrast, the Tennessee Department of Health has declined to release the number of COVID-19 deaths by county.

“We are providing numbers of deaths at the state level only due to the risk of reidentification of those individuals,” said Shelley Walker, the state agency’s spokeswoman.

Other states, however, have safely released confirmations of COVID-19 deaths by county without identifying the deceased, including Virginia, Kentucky, Georgia, Missouri, Texas, Louisiana, North Carolina, Colorado, Florida, Oklahoma, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New Mexico, Washington, Michigan, West Virginia and Iowa.

Some states provide age and sex. Others have given more information, such as whether the person had an underlying condition, or even a more specific location than county — such as a city or even workplace.

Some states are also releasing information on the current number of hospitalizations of COVID-19 patients.

Tennessee does not list current hospitalizations, but does show on its COVID-19 website how many have ever been hospitalized for COVID-19. The state explains that “(i)nformation about hospitalization status is gathered at the time of diagnosis, therefore this information may be incomplete. This number indicates the number of patients that were ever hospitalized during their illness, it does not indicate the number of patients currently hospitalized.”

The identity of nursing homes that have had confirmations of COVID-19 cases has also been shared in some states. In Colorado, a public records request shook loose this information.

Local press, local mayors have been filling in details of COVID-19

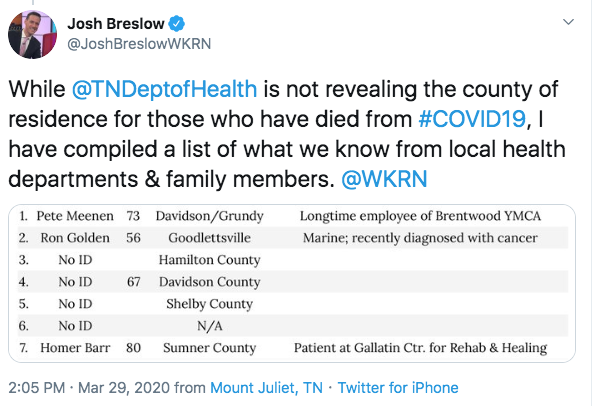

Despite the lack of information from the state, the press has been collecting data from local government officials and other sources.

For example, Josh Breslow, a reporter with WKRN Channel 2 in Nashville, tweeted on Sunday that even though the state won’t share county-by-county death data, his news station is building its own data, using on-the-ground reporting from local sources. Undoubtedly, newsrooms across Tennessee are doing the same.

Local mayors are also becoming important in disseminating information.

The Oak Ridge City Council, for example, in its meeting last week publicly discussed the available number of ventilators and beds at its local hospital. Information flowed from the fire chief as well, who assured the council that because it is specially equipped to deal with hazardous materials, it has haz-mat suits that should protect its front-line workers.

After an outbreak in nursing homes in Sumner County, Portland mayor Mike Callis shared information with the community about the number of cases, and the identity of the home. The Gallatin mayor and Sumner County Mayor also gave interviews and details about a mass outbreak in a nursing home facility in Gallatin.

The state has released some information to news reporters that are not on its website.

On Sunday, for example, the Times Free Press published this information which it said it received from the state health agency’s spokeswoman:

“As of Friday at 2 p.m., 3,823 of 11,481 — or 33% — of hospital beds were available in Tennessee, according to the state’s Health Resource Tracking System. In addition, 980 out of 1,460 ventilators, or 67%, were available.”

The state’s Health Resource Tracking System was launched first as a pilot program in 2006 under Gov. Phil Bredesen. According to its website, the Healthcare Resource Tracking System (HRTS) “manages healthcare facility bed, service and asset availability. HRTS provides for event activation and management locally, regionally or state-wide.”

And some hospitals have given out information, too.

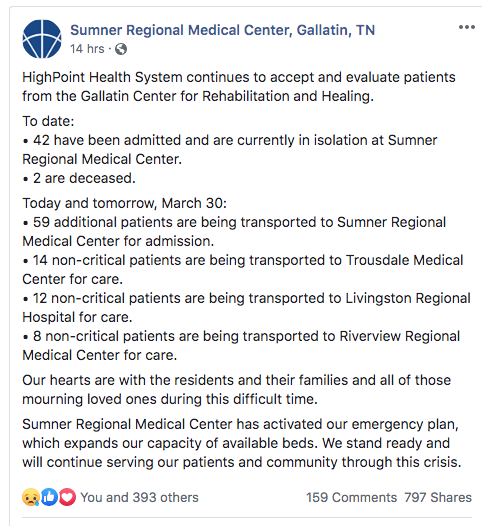

The Sumner Regional Medical Center in Gallatin, after receiving an inflow of COVID-19 patients from nursing homes, shared detailed information on its Facebook page, including how many patients had been admitted, how many were coming and how many and where non-critical were being transferred.

When the COVID-19 epidemic began, Tennessee initially only released the number of confirmed cases, but refused to release the confirmed cases of the virus by county. It switched course and eventually included on its website a count of confirmed cases by county.