Open Records Counsel gets increasing number of inquiries

By Deborah Fisher

Executive Director, Tennessee Coalition for Open Government

The number of inquiries and complaints to Tennessee’s Office of Open Records Counsel is pacing ahead of last year, with three more months to go.

The office answers questions from citizens, government entities and media about public records and open meetings law, and is authorized by law to informally mediate and assist in resolving disputes concerning open records.

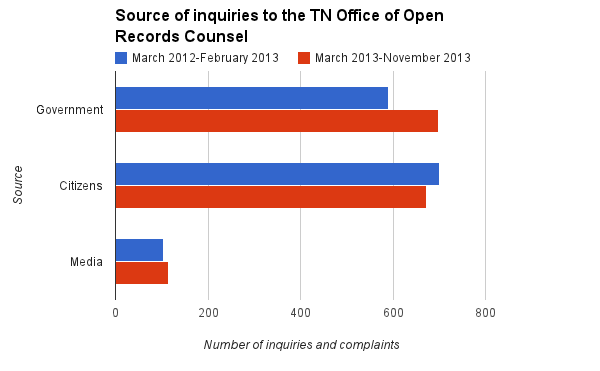

Last year, for the period between March 2012 to February 2013, Tennessee’s Open Records Counsel Elisha Hodge received 1,408 inquiries or complaints. By the end of November, her office had gotten 1,484, already a 5 percent increase.

Hodge shared those numbers in an annual meeting Monday with the Advisory Committee on Open Government, a panel made up of citizens, media and government representatives charged with providing guidance and advice to the office.

The most inquiries in the current cycle that began March 2013 have come from government entities (698), followed by citizens (672) and media (114).

That changes the mix slightly from last year when the most inquiries came from citizens (700), followed by government entities (591) and media (103).

The biggest bulk of inquiries are public records issues and Hodge noted that the increase has been pumped up recently by disputes in Hendersonville.

She noted that some of the most common public records inquiries have been about fees, access to public records by non-citizens, and the ability for citizens to bring in their own copying equipment or scanners to make copies instead of paying the government entity to make them.

The U.S. Supreme Court opinion in April 2013 in McBurney v. Young has generated questions about non-citizen access to Tennessee’s public records. In that case, the high court upheld Virginia’s right to only allow access of the state’s public records to citizens of the state, and, in other words, the ability to deny them to residents of other states.

Hodge said in a followup interview that she tells governmental entities in Tennessee who ask about giving public records to out-of-state requesters that it is discretionary.

The Tennessee Open Records Act gives only citizens of Tennessee the right to inspect and receive copies of public records. On the other hand, it does not prohibit making records accessible to non-citizens.

When the citizen makes the copy

On the inquiry about whether citizens can use their own scanners, smartphones or other equipment to make their own copies of documents, Hodge said she advises that there is nothing in Tennessee’s Open Records Act that specifically requires a government entity to allow it, but nothing that prohibits self-copying either.

She noted that records custodians have concerns about maintaining the integrity of the records, fearing that the record could be altered in some way. “Turning over an original document is a very scary proposition for government entities,” she said.

Frank Gibson, public policy director for the Tennessee Press Association and a committee member, said that citizens and media who want to make their own copies are most often just trying to save money. If the custodians knew the person making the copies wasn’t going to hurt the records – they are just going to take a picture, for example – perhaps that would alleviate the concerns, he said.

Another advisory committee member, Dorothy Bowles, representing Tennessee Coalition for Open Government, noted that a government staffer or clerk was usually present when someone was inspecting records anyway, and could be on guard for any problems.

Hodge also said she often gets questions and complaints from governmental entities about the inability to charge labor fees to prepare documents for inspection. The Open Records Act allows for a system of charging labor fees to prepare documents for copying, but the law doesn’t allow it when the records are being prepared for inspection only.

The Tennessee School Board Association had considered proposing legislation that would change that, and the comptroller’s office had also discussed it, she said. But it doesn’t appear to be likely in the upcoming legislative session.

(Both the idea of charging citizens to use personal devices to make copies, and charging citizens fees to inspect records have been issues in other states. This week, the Arizona Attorney General weighed in on that state’s public records law, saying that government could not charge fees if a person wanted to inspect public records, even if a government worker had to spend time preparing the documents for inspection such as redacting information.

(The AG also said that a citizen could not be charged a fee for using his or her own device to make copies. Dan Horne, who represents the Arizona First Amendment Coalition, told the Arizona Daily Star, that the ruling was a game-changer. “The reality is now that pretty much everybody has a smartphone,” he said.)

Also in regard to fees, Robb Harvey, a media lawyer on the advisory committee representing the Tennessee Association of Broadcasters, noted Tennessee Comptroller Justin Wilson’s new policy of setting a $25 threshold for charging copy/labor fees for public records.

The comptroller’s office had reasoned that the cost of processing payments that totaled less than $25 actually cost more than the actual fees for copying and labor.

Hodge said the waiver policy is well known within state government, and she often advises local governments who are putting together fee policies how waivers could simplify and actually save money.