Lawmakers retain public inspection of autopsy reports of minors, but prohibit release of copies

Tennessee lawmakers made a major change this year in the state’s law regarding access to county autopsy reports, prohibiting the release of such reports when the deceased is a minor and the cause of death is listed as a homicide.

However, people will be able to still see such reports during an in-person inspection — presumably at the office of the county medical examiner — as long as they do not take photos or make photocopies during the inspection.

Parents of children at the Covenant School in Nashville, who had joined to lobby on gun-control issues after the March 2023 shooting at their school, pushed the autopsy bill. It was first introduced in a special session called to deal with school shootings in August 2023, but did not pass. It was reintroduced during the regular session in 2024.

House sponsor reads emotional statement from parent

When House sponsor Rebecca Alexander, R-Jonesborough, presented the bill in committees, she read an emotional statement from the grieving mother of one of the three children killed. Alexander said that parents can protect their children when they are alive, and they should be able to protect them in death from those who would wish to see their autopsy reports.

News organizations had already obtained copies of autopsies of the three Covenant children in the months after the shooting. But one of the parents testified in a House committee that the bill would allow the parents to prevent the publication of the autopsies by those who already had received them. No local news organizations have published the autopsy reports and a simple Google search online did not immediately surface publication of any of the autopsies, but the parents have said that someone did publish at least one of the children’s autopsy report online.

The new state law’s language is admittedly confusing, but lawmakers, in the end, said they were trying to find a balance between causing anguish for parents who might see copies of their child’s autopsy reports on the internet and retaining public access to information in the reports that have long been a public record in cases of homicide.

Government is required to conduct autopsies in cases of suspected homicide

The law has stated for decades that all autopsy reports conducted by the government under the state’s Post-Mortem Examination Act are public documents. The types of autopsies required to be conducted by the government include those in which foul play or criminal activity is suspected or in cases where the death is suspicious. (Not all autopsies are done by the government; sometimes a family will pay for a private autopsy when trying to determine the medical cause of a person’s death. Those private autopsies are not public documents.)

The bill that passed this year carves out an exception for autopsy reports of minors who died in a homicide, stating that these are not public documents. It says the reports can be released only if the minor’s parent or legal guardian is not a suspect in the minor’s death and consents; if a court orders the release upon a showing of good cause; or if another state or federal law requires such release.

Why keeping autopsies open is important

The provision retaining the ability of members of the public to inspect such reports came after discussion between lawmakers and the Tennessee Coalition for Open Government, the Tennessee Press Association and the Tennessee Association of Broadcasters. While many types of people access the reports, such as family members, private investigators and researchers, journalists regularly request to see autopsy reports done by the government when there is a question of criminal activity, foul play or a suspicious circumstance, or when the death involves a public official or public figure. For example, they almost always request to see the autopsy of someone who died at the hands of police or in government custody to check whether public statements by authorities match up with the examination of the body by the county medical examiner.

During the discussion on the bill, some lawmakers questioned why anyone should have access to a government-ordered autopsy report when murder is involved, suggesting that police can release any information that the public needs to know. In cases in which someone is charged with a crime, an autopsy report also may come out during a public trial.

Bill affects children who are killed while in state custody, such as foster care

Tennessee Coalition for Open Government testified against the bill, drawing attention to the fact that the legal guardian of some children under 17 is the Department of Children’s Services. Thousands of children live in DCS facilities or are placed in foster care homes. When such a child is killed, the children’s services department would have to consent for the autopsy to be released to anyone, including to any family members of the dead child. TCOG believes this will reduce transparency in cases of deaths of children who are in the custody of the government.

TCOG’s testimony also made clear that the value of government autopsies in a homicide is information that correctly identifies the killer. For example, autopsy reports can show how a person died, the proximity and location of the killer when inflicting the wounds and the type of weapon used.

News media reports on autopsies have gotten cases reopened, led to new convictions, cleared people in a crime and refuted what police said about the person’s death, including claims of self-defense by the killer.

Compromise keeps inspection of murdered children’s autopsies

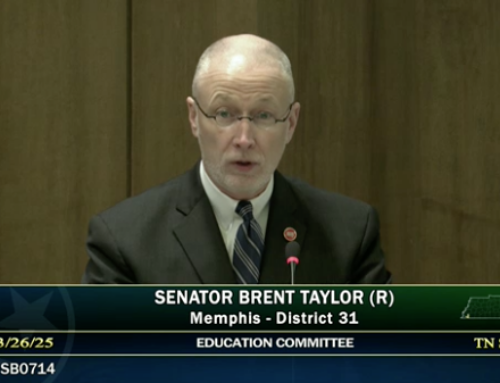

Despite interest among some lawmakers to retain the current law, in the end, the desire to be responsive to the parents of the three children who were killed in the Covenant shooting helped the bill pass easily through the House with support of House leaders, including House Majority Leader William Lamberth. After the Senate amended the bill to retain in-person inspection, the House agreed to make a change, largely at the urging of Lamberth, and wrote its own amendment for in-person inspection. The amendments of each house were largely the same in intent, but differed in that the House amendment kept language that said the autopsy reports of minors were not public documents, a provision that the Senate amendment did not have. The Senate, however, agreed to go with the House version once the bill reached its floor.

“The House bill clarifies that the autopsy can still be inspected by the public, which was the intention of the state and local committee amendment,” said Sen. Richard Briggs, chairman of the Senate State and Local Committee, in explaining the adoption of the House version. “With the explanation we have discussed with the bill’s sponsor about the Senate bill … he feels that the House amendment clarifies it even better.” Sen. Shane Reeves, R-Murfreesboro was the Senate sponsor.