Judge rules against Knox County sheriff in public records case, puts department under court orders

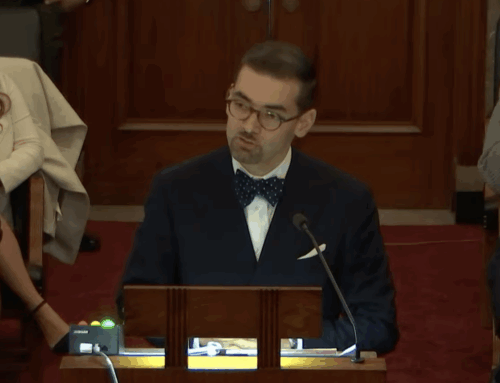

In an important win for access to public records, Knox County Chancellor John Weaver found the Knox County Sheriff’s Office violated the public records law in its responses to a sociology professor seeking access to records related to immigration enforcement.

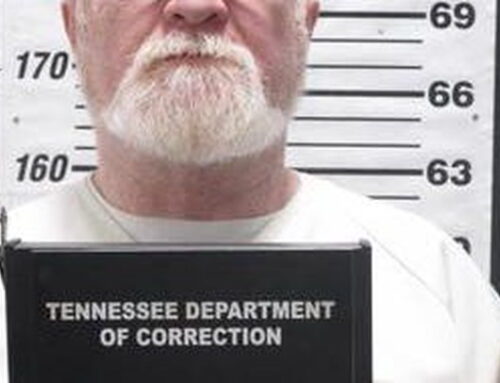

After a public records case that stretched on for a year, Weaver issued a court order on April 9 in Meghan Conley v. Knox County Sheriff Tom Spangler that requires the sheriff’s office to comply with provisions of the law governing responses to public records requests, produce records that it had not yet produced and implement a new system to enable public inspection of arrest records.

Weaver’s order also prohibits the sheriff’s office from “treating any written request for inspection or copies generally phrased in terms of information sought as insufficient for lack of specificity or detail.”

In addition, Weaver said the Conley is entitled to an award of attorney’s fees and costs — an award allowed when a government entity is found to willfully violate the public records law.

Also see these news reports:

Knox County sheriff tested novel approaches to public records law

The Knox County Sheriff case tested several novel approaches to the public records act by the sheriff’s office. One of those was the interpretation that allowed it to deny requests that were not specific enough, and then turn around and deny requests because the specificity of the request would require the agency to sort through records to identify the specific records requested.

The sheriff’s office also revealed during the bench hearing a policy of automatic deletion of all employees’ emails after 30 days unless the employee determined the email needed to be retained as a public record and printed it out.

The broad and systematic records destruction came to light when the sheriff’s office explained that upon Conley’s request for emails, the department only searched emails from the most recent 30 days, not emails that might have been printed out or retained by individual employees. The department insisted that if someone had wanted those emails, they had to specify “archived” emails, instead of just asking for “emails”.

Weaver concluded that a public records request for “emails” was sufficient to cover all emails.

But in a comment that echoed the chancellor’s persistent questions during the trial about the deletion policy, Weaver wrote: “No issue has been raised in the case as to the adequacy of the KCSO’s policy of leaving each of its employees in charge of determining whether a record is a public record and whether a record may be destroyed without going through the Public Records Commission.” In the end, Weaver left the potential legal problems with the practice alone.

Weaver rejects sheriff’s arguments for denying requests

Overall, Weaver in his 42-page Memorandum of Opinion, broadly laid out the requirements of the public records law found in both statute and court rulings while also noting that the case itself was “replete with tortuous twists and turns.”

He said the predominant legal issue in the case was the “sufficiency of Professor Conley’s requests for public records,” and spent an important part of the opinion explaining why the sheriff’s department’s view of specificity-based denials was flawed.

The sheriff’s office had taken the striking position that many of Conley’s requests would require them to read through every email or look through all files of its 1,100 employees and sort through them to compile records that may be responsive.

Weaver noted that the sheriff’s office could easily inquire of its 1,100 deputies as to whether they have any particular records by sending out a blanket email. “However, the more important issue is whether the burden of indexing and producing records may excuse a governmental entity from the mandate of the Act that ‘[a]ll state, county and municipal records shall, at all times during business hours…. be open for personal inspection by any citizen of the state, and those in charge of the records shall not refuse any such right of inspection to any citizen, unless otherwise provided by state law.”

“The KCSO’s explanation is that there was no way to identify the specific records without going through each and every record of approximately 1,100 employes. However, by maintaining no indexing or means of access, there can be no access to public records. That does not appear to be in accord with the legislative mandate that all public records, at all times during business hours, be open for public inspection… It also appears to be contrary to the Act’s ‘crucial role in promoting accountability in government through public oversight of governmental activities.’

“If there is no reasonable way for the public to access the public records, the public cannot use them to oversee governmental activities.”

Generally phrased requests do not render a request invalid, Weaver says

In one instance, Weaver describes a specificity-based denial of Conley’s request for communications regarding the sheriff’s 287(g) program and intergovernmental service agreement with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement as setting off a series of unfruitful communications.

“Instead of working out, face-to-face, the facilitation and mechanics of Professor Conley’s inspection, the parties embark upon a course of Professor Conley’s pitching out requests and the KCSO’s calling balls and strikes.”

Weaver concluded that requests that were “generally phrased in terms of information sought” do not render the request insufficient for lack of specificity or detail, and went on to find that many of Conley’s requests were sufficiently detailed under the law to enable the sheriff’s office to retrieve them.

He also said that while the law does not require a government entity to manually sort through records and compile information gained from the records, “that does not relieve the governmental entity from permitting ‘[a] citizen appearing in person’ to ‘inspect the records and retrieve the information himself or herself’ ” from those records.

“Moreover, where a citizen requests particular documents maintained in voluminous files, the governmental entity may be required to go through the files and manually retrieve the documents requested…” Weaver wrote.

Sheriff wrongly limited access to arrest records

The sheriff’s office had argued that it refused Conley’s request to inspect arrest records because it did not have a system to allow public inspection. Instead, the office suggested she request copies through a records request button on its website. But at the trial, it came out that only a certain number of copies were available a day through this method.

Weaver said a governmental entity cannot limit access to obtaining copies and “has the burden of keeping the arrest records, for which there is constant public demand, open for inspection.”

To solve the issue, Weaver ordered the sheriff’s office to begin steps to implement a system, “either manually or through a computer program or system that will enable it to produce its arrest records on a current basis for inspection and viewing by citizens with the confidential information redacted…”

The order calls for the system to be ready within a reasonable amount of time, but says the time limits are suspended as long as the Governor or Knox County Health Department has mandated the closure of nonessential business to the public because of coronavirus.

Sheriff’s office attempt to make redaction costs a legal issue gets no traction

The issue of making arrest records available for inspection led to another side excursion in the case, which surely must have been one of the “torturous twists and turns” Weaver mentioned in the opening comments of his ruling.

During the course of answering why the sheriff’s office did not allow Conley to inspect arrest records, the office speculated it would have been cost-prohibitive for Conley because even though she was inspecting the records, and not seeking copies, she would still have to pay for redaction of the arrest reports. Journalists who were covering the trial immediately seized on the statement, and wrote stories about the sheriff’s position.

In Tennessee, the public records statute says that there can be no charges for viewing records, but allows labor charges if someone requests copies of public records. The “free inspection” of records was an issue in 2015 when two lawmakers proposed changing the law to allow labor charges for compiling records when someone wanted to inspect and not just when they wanted copies. After a summer study requested by lawmakers and conducted by the Office of Open Records Counsel that included public hearings across the state (including in Knoxville), the lawmakers withdrew their proposed legislation in the face of overwhelming support to continue free inspection.

Weaver declined to rule on the redaction issue, which Conley’s attorney Andrew Fels had argued in his closing statement needed no action.

In the ruling, Weaver says that there is nothing in Professor Conley’s petition concerning redaction, and she sought no relief or proposed conclusions of law regarding it. The chancellor also said that the sheriff’s office never assessed a charge to Conley for redaction.

However, Weaver did spend about four pages of his opinion discussing the arguments. He said that initially the “statutory framework” presented by the sheriff’s office “seemed persuasive for KCSO’s position that it was entitled to charge for redacting, whether for copies or for inspection only.”

“However, irrespective of the forgoing analysis, it appears that the Tennessee Court of Appeals has held that a governmental entity may not charge for redacting where a citizen requests inspection only and not copies,” citing Eldridge v. Putnam (2002).

He goes on to also offer the more recent ruling in Taylor v. Lynville where the Court of Appeals ruled that it was unlawful to charge the requestor anything in making records available for inspection.

Finally, Weaver said that the sheriff’s office’s contention that it could charge for redacting documents to make them available for inspection is “directly contrary to the opinion of the Tennessee Office of Open Records Counsel.” (Op. No. 8-14).

Sheriff’s office could be held in contempt if it doesn’t comply with judge’s orders

Many of Conley’s requests for relief were not granted. Conley had asked for injunctive relief that Weaver said lacked the precision necessary for enforcement.

“The Act does not authorize the court to issue a broad and blanket injunction for the purpose of placing the court’s contempt power behind undefined, prospective, future violations of the act.

“However, any failure to comply with the specific and precise orders of this court will be enforceable by the court’s contempt power. This opinion may also be used on the issue of willfulness in the event of any future violations of the Act concerning the matters addressed herein.”