Judge: Nashville board violated Open Meetings Act by failing to provide adequate notice of soccer stadium vote

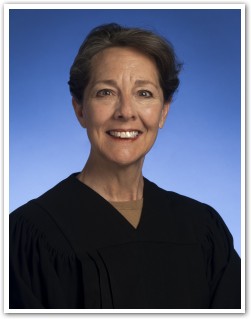

A Davidson County chancellor ruled that Nashville government violated the Open Meetings Act in 2018 by failing to provide adequate notice of a Metro Sports Authority board meeting in which a $192 million construction contract was signed for a soccer stadium.

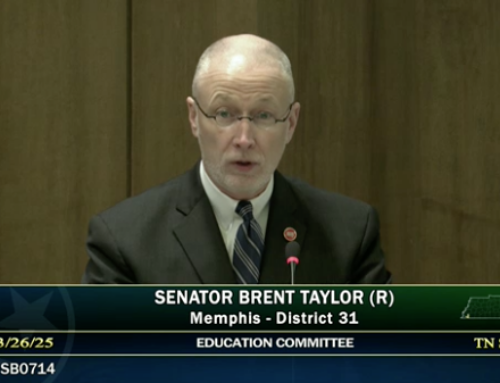

Chancellor Ellen Hobbs Lyle in her June 25 order ruled the action taken in approving the contract with Mortenson/Messer Construction Company is void and of no effect, noting that the “law in this area is clear and unequivocal.”

She said the Sports Authority Board would have to reschedule the meeting, provide adequate public notice and conduct another vote on the contract.

Lyle found that the 48-hour noticed given by the sports authority board did not provide enough time for the public to become aware. Another factor was that the sports authority board members knew the issue was of significant public interest.

The Tennessean characterized the ruling as “more of a swat rather than a setback for stadium plans,” considering that the board is likely to simply call and meeting and vote to ratify its earlier decision.

Judge outlines evidence proving violation

The Tennessee Supreme Court in 1974 set the standard on the meaning of adequate notice not long after lawmakers passed the Open Meetings Act requiring it. In the very first challenge to the law, the Court ruled in Memphis Publishing Co., v. City of Memphis that adequate public notice is “such notice as based on the totality of the circumstances as would fairly inform the public.”

That standard has meant that any court evaluating a claim of inadequate public notice of a governing body meeting must examine the “totality” of the evidence in making a decision.

The bench trial on the open meetings violation was held June 15-17 via Zoom. (Video here.) See the judge’s final order in Leo Lillard et. al. v. Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County.

In her order, Lyle outlined the evidence of the notice for the meeting. She wrote that the “cryptic content of the notice” and the inadequacy of the timing of the notice 48 hours before the meeting “establish that the totality of the circumstances is that the notice provided of the Nov. 1, 2018 meeting did not ‘fairly inform the public.’ “

Other proof was cited, including that the meeting was a special called meeting not held at the board’s regular time and only one member of the general public attended the meeting — the rest had a vested interest in the construction project.

Lyle said the proof also showed that the customary advance time for public notice of the sports board meetings is five days, and that there was no emergency or urgency which compelled a shorter notice. And even though notice was also emailed to subscribers who had signed up to receive notice, only 30 subscribers had opened the innermost URL link containing the meeting time and agenda description.

Lyle also said that Metro government failed to show that “wasted costs or defaults or forfeitures on Project agreements” would occur with the voiding of the action, nor would the contract have to be re-bid.

Order address issues that are common complaints of citizens

The order offers a tour of law on adequate notice for public meetings.

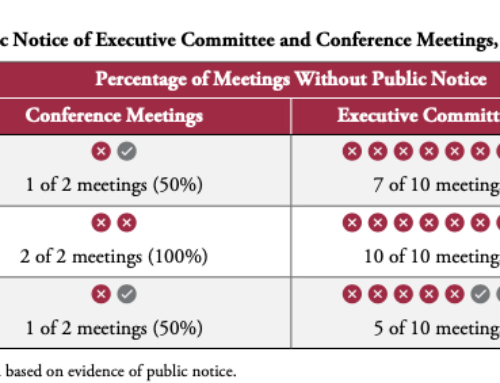

A common complaint of citizens is that government does not provide adequate notice of meetings. The most common complaints are that meeting agendas lack enough description for the public to understand the matters to be decided; that notice is not posted in places where people can see them; and that often, notice is not posted in enough time to make plans to be there.

In looking at the location, timing and content of the notice, Lyle quoted the 1999 ruling in Englewood Citizens for Alternative B v. Town of Englewood by the Court of Appeals.

In that case the town held a special called meeting to choose the route for widening a highway from two lanes to four lanes.

The court found that Englewood’s two days notice was not adequate to to give citizens the opportunity to become aware of and attend the meeting. The Court also found that Englewood’s notice did not “reasonably describe the purpose of the meeting or the action to be taken.”

Lyle said that the Sports Authority Board’s characterization of its agenda — “Consideration of Construction Management Agreement — was not misleading, but is somewhat “cryptic” and “bereft of any explanation.”

At one point in the trial, the issue of why a citizen might want to attend a public meeting came up.

Dominy admitted that the board did not allow public participation, such as through public comment, but “I would have liked to attended so that I would have had the opportunity to speak with some of the board members before or after the meeting.”

The attorney for the plaintiffs told the newspaper that the city could have remediated this sooner and on their own, without a trial. “As is typical, Metro doesn’t want to admit they made a mistake. They handled this meeting wrong,” attorney Jim Roberts was quoted as saying in the story.

Metro’s lawyers had pressed one of the plaintiffs, former Metro Councilman Duane Dominy and an opponent of using the fairgrounds for the stadium, about his motivation. Dominy replied that he just wanted government to follow the law.

“Actions that violate the public trust call into question our government as a whole. My concern is the failure of the government to honor its policy and law,” he said.

Dominy also has said the city violated its charter in moving ahead with the project on the city’s fairground property. A separate lawsuit on that issue by the Save Our Fairgrounds organization is scheduled for an August trial.