Judge says Sumner County Schools denied public records request, but not willful

Sumner County Judge Dee David Gay said Thursday in preliminary findings that Sumner County Schools denied a public records request from open government advocate Ken Jakes, but that he heard no proof that showed the district was willful in its actions.

Gay said he would make a final ruling in November on whether the school district violated the Tennessee Public Records Act when it denied Jakes’ request on the basis that he did not follow the local district’s requirement that he make the request in person or through the U.S. Postal Service.

Jakes had emailed his request, following up with a voice mail, asking in March 2014 to inspect the school district’s public records policy. After the lawsuit was filed, the school district finally provided the policy in February 2015, nearly a year later.

While Gay said that he did not think the district’s actions were willful – a finding that would mean Jakes would not be able to recover attorneys’ fees from the district – he did say he would hear further arguments in briefs by Jakes’ attorney, Kirk Clements, on the matter.

He asked both attorneys to submit briefs by Sept. 1.

The judge pointed to the Best Practice Guidelines on the Office of Open Records Counsel website, noting it called for governmental entities to use the most “economical and efficient method of producing records.” He noted how it would have been “great” if the school district had just emailed back a link to the record requested by Jakes which was on the school district’s website. And he called the school board’s requirements a “Pony Express attitude instead of a telegraph attitude.”

“We’re in the 21st century. And considering the Best Practice Guidelines, why does anybody require a policy where you send a letter or you come in person?”

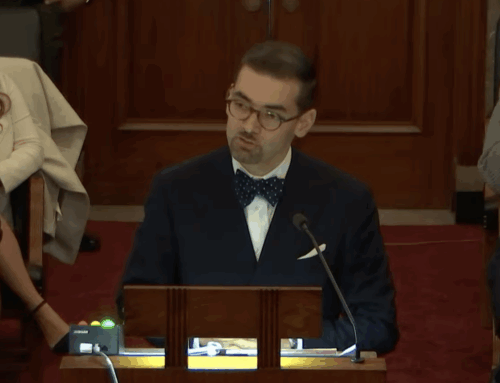

The school district’s attorney, Todd Presnell, argued that local government entities have the discretion to set their own policies on how they receive requests, and the way to handle criticism of the policy is not through the courts, but through the legislative process – going before the school board or through the elected school board members.

“That is a policy decision,” Presnell said. “If they want to require through a Pony Express method or a website, or allow anything like that, that is up to them, and not up to a court to come in and read into the statute what is not there.”

Presnell warned that if the judge ruled in a way that required that the school district accept email, it would open up the door to require government agencies to accept public requests – no matter how they were submitted.

“Where does this end? Does a text message to a cell phone of any employee constitute a valid request? What about a fax machine? Voice mails? What about leaving a written note on the school office’s front door?”

Clements argued, however, that the law does not give local government entities authority to restrict how an individual makes a public records request, outside of allowing a check for identification and setting policies related to making and charging for copies.

“Now, if someone posts a note on the door of the central office, is that a records request? Well, if the school board receives it, why wouldn’t it be? Here’s my point. If the school board doesn’t receive the request, they have no legal obligation…

“The issue is not how it is sent, it is whether or not it is received, which is not in dispute in this case.”

He cited cases where the Court of Appeals rejected local government rules that put “form over substance”, including a recent opinion in Alex Friedmann vs. Marshall County. The courts have said that if a citizen can sufficiently identify documents in a request, a personal appearance is not required. In the Friedmann case, the court reversed a trial court ruling, and said that the sheriff’s office condition that Friedmann make his request in person violated the Tennessee Open Records Act.

Although the school district’s own attorney, Jim Fuqua, testified that former Open Records Counsel Elisha Hodge told him that there was nothing in statute that required a governmental entity to accept requests by email, Clements said, “He didn’t articulate the legal foundation for her opinion that if you receive an (public records request by) email, you can just ignore it.”

The judge had harsh words for Jakes, saying his communication with Jeremy Johnson, the school’s community relations official who handles public records requests, was “some of the rudest, most arrogant emails I’ve ever seen.” He also said Jakes had a “conspiracy mentality” that was not borne out by proof in the case.

“However, those issues with credibility are not going to distort the essential facts in this case.”

The judge was referring to email communication Jakes sent to Johnson, threatening legal action if Johnson did not comply with the public records request. Jakes testified that he had been trying to show he was serious.