Judge cleared release for many Covenant shooting police records despite copyright ruling on manifesto

Parents and others with the Covenant School attend a public records hearing in June 2024 in a case involving whether police must release its investigative records into the March 2023 shooting at the school. Many records have been at issue, including the shooter’s manifesto and other writings. (Screenshot from video of hearing.)

Two weeks ago, a Davidson County judge issued a major ruling in a public records case involving records from the police investigation into the March 2023 shooting at the Covenant School in Nashville. Six people were killed, including three children.

So what records about the Covenant school shooting can be released and when?

There were three major parts of Chancellor I’Ashea Myles’ ruling. The part that got the most attention was her copyright decision. Myles decided that Nashville police were prohibited under the federal copyright law from releasing the so-called “manifesto” and other writings and video created by the shooter that police had retrieved in her car and home.

While this is not the first time in the United States that copyright has been asserted to prevent the release of public records, this may be the first time a judge has found that criminal evidence collected by police and relevant to a homicide can be blocked from release because it was the intellectual property of a killer. Public records advocates — and those concerned about police and judicial transparency — are rightly concerned.

But police have many more records than just the shooter’s writings, and these other records are likely to be of high interest to those following the Covenant shooter case.

Some of those documents have been leaked to a conservative news outlet, The Tennessee Star. One of the most interesting leaked documents is a police summary of the shooter’s medical records at Vanderbilt Psychiatric Hospital that includes notes that she told her doctor or doctors at least three times she was thinking of being a school shooter. She also told her doctor she wanted to kill her father.

It is unclear when police will release these records or information about them. Police may still yet assert that the shooter’s psychiatric records fall under a medical record exemption to the state public records law and refuse to disclose or even discuss it. But I think this would be a disservice to the public.

If the shooter told her psychiatric doctors of her plans, an obvious question is why it was not reported. Or was it reported and no one followed up? Or was the information just not taken seriously? Police likely have much more information, including notes from interviews with people involved. All of this should come to light.

This is just one record we know about because it was leaked. There could be other consequential records that would shed light on what led up to the shooting and opportunities in which people could have acted to stop it.

Remember, the public records requests that started the case were made in the immediate weeks after the shooting. But the investigation continued for more than a year after that. The judge reviewed records in camera at an early point in the investigation. So many more records have been created, some of which may not have been reviewed by the judge.

One factor could complicate release of information: an appeal of the judge’s decision. If the appeal is limited to the rulings on the shooter’s writings, police could go ahead and release other records that are not the shooter’s writings.

There are three main parts to the public records ruling to consider:

- Investigative records

- School security

- Copyright law

I will delve into the copyright ruling last as it is the most complicated.

Police Investigative Records

Normally in Tennessee, evidence collected by police and others parts of a police investigative file such as notes and summaries are public record after a trial and any appeals are over. If there are no criminal charges and no public trial, the information becomes public after the investigation is over.

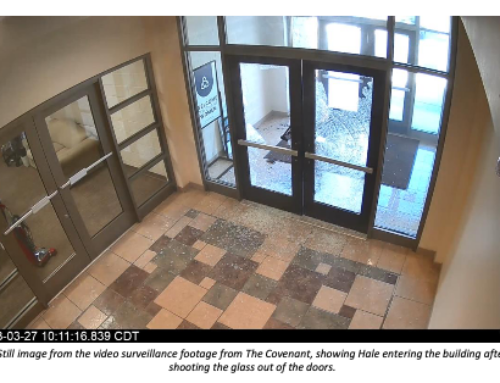

In the days following the March 27, 2023, shooting, police announced that they believed the shooter, who was killed by police at the scene, acted alone. They also announced they had recovered a manifesto and other material in her home. News media and other organizations began requesting records. Police refused to release any records, saying the case was still under investigation.

On May 1, 2023, the first petition was filed challenging the police denial of records, largely arguing that the investigative exemption does not apply because police were not contemplating charging anyone else and the shooter was dead. Eventually, there were four sets of petitioners who filed lawsuits, including two news organizations and a state senator.

The judge ruled that Nashville police properly asserted the investigative exemption, relying on declarations by police.

“While this Court is mindful of the Petitioners’ argument that if a court were to blindly accept a bare, unsupported assertion that some amorphous investigation is ongoing, this could lead to abuse of the Rule 16 exception (investigative exception). However, that is not what Metro has claimed or asserted in this case… Police Lieutenant Brent Gibson offered sworn testimony that the police are investigating specific points — whether the assailant received any assistance with planning the attack or with weapons purchases, and whether there were any co-conspirators… Gibson further stated under oath that he anticipated the investigation would take about four more months to conclude. This is a far cry from a scenario in which police might state only that ‘something’ is being investigated, and that such investigation might continue indefinitely.” (Declaration was on March 1, 2024.)

Judge Myles ruled that police had carried its burden of demonstrating an open investigation and contemplated criminal proceedings against others. Thus police do not have to release records until the investigation is finished.

It should be noted that the four months estimated by Gibson were up on June 1. However, in a mid-June hearing on the case, the city’s lawyer stated the investigation was still ongoing but would be finished “soon.”

School security

When denying access to the records, police used the investigative exemption as well as an exemption related to school security. The school security exemption made “information, records, and plans that are related to school security, the district-wide school safety plans or the building level school safety plans” not open to public inspection.

Police had said that they intended to keep confidential some of the school-specific information found in the shooter’s writing, such as any diagrams or building information.

However, arguments about what should be kept confidential under this and another school security statute ballooned after the judge allowed parents of the Covenant children (including those who died as well as those who survived), the school and the church to intervene.

These intervenors believed the release of any of the shooter’s writings would inspire copycats, and thus lessen the security of the Covenant school as well as all other schools.

The parents, school and church acknowledged in court that they had not seen any of the writings and did not know what was in them. However, they argued that statutes related to school security, including the one police cited, were broad enough to prohibit the release of all of the shooter’s writings. The judge disagreed with some of their arguments but found that the school security exemption that was cited by police could be used to keep the shooter’s writings confidential.

“[T]he General Assembly did not include any qualification or limitation for the type of school security information, records and plans, which are subject to this exception. Instead, the exception is left with a broad construction to encompass all information related to the security of any school,” the judge wrote. “…This Court would be hard pressed to find that the original and complied (sic) writings, photos, video content, information, original and assumed plans and artwork of an individual whose intent and plan was to cause and inflict harm on the innocent in a school setting would not be related to school security and thus exempt from disclosure.”

She noted the two competing experts relied upon by the parties had “diametrically opposed views on the long- and short-term contagion effects of the writings” but said she found the arguments surrounding copycat killers more convincing. She ruled “that materials and content created and/or compiled by (the shooter) as she studied and devised her plan, not only against this school but others, is information related to school security. This Court finds the possibility that these materials could be used by a copycat shooter… to be a real security concern for schools here in Tennessee and across the nation.”

The ruling appears to make all of the writings and material of the shooter confidential. The only public glimpse of the writings comes, again, from leaked documents published by The Tennessee Star, which has written extensively about the 80 pages it has received. From this, we know that not all of her writings have to do with her specific plans on attacking the school, but rather her thoughts and notes about her interactions with others, including her father, and her thoughts about herself.

Copyright ruling — “a matter of first impression”

The part of the ruling drawing most attention was about the federal copyright act.

It is not unusual for police to use writings or other tangible material such as audio and video recordings created by a person to show motive or intention in a crime or to discover other information. This is why they get search warrants to collect it. You often see and hear about such material in a public trial. Prosecutors use it to show intent; defense attorneys use it to show something else, maybe insanity.

I was in the courtroom during a hearing in the case when the defense lawyer for the shooter’s parents, David Raybin, appeared. The shooter’s parents were not a party to the public records case, but Raybin told the judge that they had inherited their daughter’s writings, that the writings were intellectual property and that they planned to transfer the writings to the parents of the Covenant children in a trust. The trustee would be Brent Leatherwood, one of the parents of the survivor children.

The purpose of the move was to allow the Covenant parents to claim copyright interests and prevent their release — an interest likely shared by the shooter’s parents.

It was a stunning announcement. Some described it as a clever way to keep the so-called manifesto confidential.

The judge noted in her ruling that the arguments in the case presented “new theories of law.”

“[W]hether a valid copyright is an exemption to the (Tennessee Public Records Act) is a matter of first impression in Tennessee,” she said.

Myles reviewed the shooter’s journals, photographs, artwork, writings and video which Nashville police collected during its investigation and ruled that “some portions of the materials … are the original works of authorship” of the shooter.

Despite questions raised over the validity of the steps taken to assert copyright, the judge agreed that the shooter’s parents inherited the shooter’s “intellectual property interests,” that they had properly transferred these to the Covenant children, and that the children’s parents now had exclusive copyright interests.

The state judge also examined the federal copyright statute. One of the arguments from those seeking the records was that federal courts, not state courts, have exclusive jurisdiction over copyright claims. But this did not deter the judge from ruling that some of the shooter’s material, though not all, met the definition of copyrightable material. And though she didn’t identify what specific records fell under copyright and which didn’t, she said that police would “abridge the rights” of the Covenant children were they to release the parts that are covered by copyright.

‘Fair use doctrine’ not an issue in public records case, judge says

The petitioners seeking access to the records, including two news organizations, also had argued that the parents could not assert copyright interests because they had not registered the federal copyright. But the judge ruled that registration is only “germane to the amount of recoverable damages in a copyright infringement case” and not relevant to the public records case before her in state court.

She also dismissed arguments made related to the “fair use” doctrine. The fair use doctrine favors use of materials protected by copyright if it is used for criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship or research. The most important factor in determining fair use is whether or not the use diminishes the market for or value of a copyrighted work.

The fair use argument, the judge wrote, is to be brought as a defense to a federal copyright infringement action. This also was not relevant in the public records case, she found.

The copyright decision could prove to be most consequential of the case for future public records disputes. Will this be used in criminal cases going forward to keep evidence from the public? Will government start claiming a copyright interest in materials to keep confidential information that it previously would have released? In immediate terms, the judge’s failure to specify the exact documents of the shooter covered by copyright leaves open the question of who ultimately decides. Will it be police? Or the parents?

What’s next

One or more of the parties may appeal the ruling to the Court of Appeals.

If so, the case will continue. If the appeal is limited to the shooter’s writings and other material, it’s possible police would release hundreds of other documents about their investigation.

If there is no appeal, police will have to determine if any of the shooter’s writings can be released. They may conclude that all of the material “relates” to school security or is intellectual property and cannot be released under federal copyright law.

But, aside from the shooter’s writings, I think the judge has cleared Nashville police to release everything else.

These records could include information that reveal missed opportunities in stopping the shooter, such as the leaked psychiatric records seem to indicate. This is what the public deserves to know — what should we be doing differently in assessing threats of school shootings. We can do nothing for the people killed, but we can try to prevent school shootings in the future.