An Appeals Court finds that regulating high school sports is a government function, so the regulator should be subject to open records law.

Should the agency that regulates high school athletic competitions in Tennessee – making rules, conducting investigations, deciding eligibility and collecting millions of dollars in gate receipts – be subject to the same public scrutiny as public high schools and school boards?

The Court of Appeals in Nashville said yes in a significant April 30 decision that opens up records of an organization that touches nearly every community in the state.

The City Paper in Nashville two years ago sought records from the Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Association’s investigation into recruiting and tuition violations at the elite private all-boys high school, Montgomery Bell Academy.

The court adhered to the “functional equivalent” doctrine in ruling that the TSSAA is subject to the state’s Public Records Act.

The doctrine was first established in Tennessee in 2002 in a case out of Memphis involving an agency that received millions in state dollars to screen low-income children for government-subsidized day care and connect them with services.

The Commercial Appeal sued to gain access to its records, wrote stories, and the company’s executive director eventually went to prison for siphoning off hundreds of thousands of dollars in an embezzlement, tax evasion and money-laundering scheme.

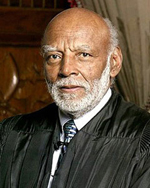

Tennessee Supreme Court Justice Adolpho A. Birch Jr. explained the reasoning when he wrote the opinion:

“…the public’s fundamental right to scrutinize the performance of public services and the expenditure of public funds should not be subverted by government or by private entity merely because public duties have been delegated to an independent contractor. When a private entity’s relationship with the government is so extensive that the entity serves as the functional equivalent of a governmental agency, the accountability created by public oversight should be preserved.”

Since then, media and citizens have sought, mostly successfully, to use the factors established in Memphis v. Cherokee Children & Family Services Inc. to obtain records from agencies that are closely intertwined with government through contracts but not government agencies themselves.

Other functional equivalent cases

The Tennessean successfully used the functional-equivalence doctrine in 2006 when it wanted the settlement agreement that arose from some cheerleaders being secretly videotaped in Bridgestone Arena’s dressing rooms.

Powers Management, a for-profit company that runs the arena under a contract with the Nashville Sports Authority, argued it was an independent contractor not subject to open records.

In another case in 2009, Corrections Corporation of America, which houses prisoners for state and local governments, was found to be the “functional equivalent” of government after a public records lawsuit by Alex Friedmann, a former prisoner and now an editor with Prison Legal News.

In East Tennessee, the Newport and Cocke County Economic Development Commission was found to be the “functional equivalent” of a governmental agency after an Appeals Court remanded the case back to the trial court to examine the issue.

Factors in the TSSAA decision

TSSAA argued it does not receive government money to run the state’s junior and high school athletic interscholastic competitions. But Chancellor Claudia Bonnyman noted at the trial court that the vast majority of its $5 million budget comes from gate receipts and contracts at tournament games held in public arenas – money that “local schools would be collecting” if TSSAA were not.

The appeals court, in the opinion written by Frank G. Clement Jr., also pointed out that public officials exert significant control over the TSSAA’s activities. Its governing boards that write the rules and decide what and how to enforce are made up of principals, assistant principals or superintendents, mostly from public schools.

Perhaps most important was the appeals court finding that regulating school athletic activities is a government function recognized as such by the State Board of Education who had formally designated TSSAA as the coordinator and supervisor in its own regulations.

In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court had found TSSAA in 2001 to be a “state actor” for constitutional purposes under the Fourteenth Amendment in a case involving Brentwood Academy.

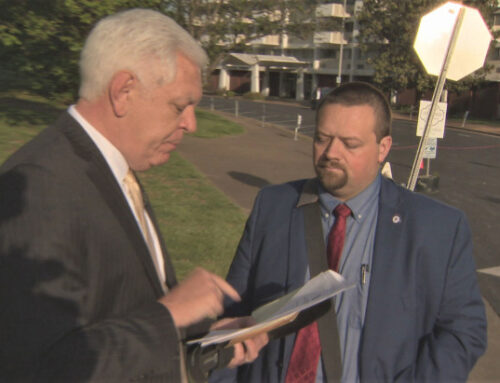

“Most of the other entities found to be functional equivalent were performing some function under contract with a government agency. That is not true in this case,” said longtime City Paper attorney John P. Williams with Tune, Entrekin & White. “In this case, the entity found to be the functional equivalent was performing a regulatory function.”

What’s not a functional equivalent

There has been one case since Cherokee in which the agency was found not to be a functional equivalent of government, Gautreaux v. Internal Medicine Education Foundation Inc.

In that 2011 case from Chattanooga, the Tennessee Supreme Court said the education foundation acted as a bookkeeper for the University of Tennessee College of Medicine-Chattanooga, a ministerial duty that was distinguished from handling a residency teaching program itself.

The decisions highlight the court’s thinking in determining who is a functional equivalent of government – the level of government funding, the amount of involvement by public officials in running the program, and the actual function of the entity itself.

TSSAA eventually announced fines and penalties against Montgomery Bell Academy saying it had violated eligibility rules for several years by playing athletes it had recruited or whose tuition had been paid by donors.

It took away two state championships and ordered a two-year probation.

Opening up the records behind the investigation – and opening up TSSAA in general – will give the public and the media an opportunity to shine light into what Steve Cavendish, the editor who brought the lawsuit, says have been opaque processes.

“They’re the only game in town,” Cavendish said. “If you are a high school athlete in Tennessee you have to be subject to the TSSAA. And that’s a lot of power.”

Written by Deborah Fisher, executive director of the Tennessee Coalition for Open Government. You can sign up to receive notification of her blog posts on open government at www.tcog.info, or reach her at [email protected].

Note: Steve Cavendish became news editor of Southcomm Inc.’s Nashville Scene when its sister publication The City Paper folded. Cavendish is on TCOG’s board as a representative for the Middle Tennessee Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.