Should execution drugs be a state secret?

By Deborah Fisher, Executive Director of Tennessee Coalition for Open Government

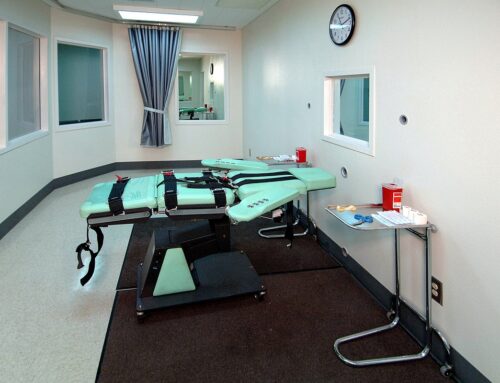

Does the public have a right to know about the drugs used to execute death row inmates?

This question has been raised in recent months in court in at least three states, two of which recently enacted new laws or protocols to keep secret from citizens the source of execution drugs.

In 2011, at least six states, including Tennessee, had their execution drugs seized or taken by the DEA after it became clear that the drugs had been imported illegally.

States have sought to keep their new suppliers secret, reasoning that the companies might be harassed or otherwise influenced to shut off supplies if the public became aware of them.

Tennessee added an exemption in the Tennessee Open Records Act eight months ago in April to exempt from disclosure “an entity” directly involved in an execution.

Previously, the law allowed only for the names of people directly involved – such as those on the execution team – to be kept confidential.

The updated law explains that the entity could be one “involved in the procurement or provision of chemicals, equipment, supplies and other items for use in carrying out a sentence of death…”

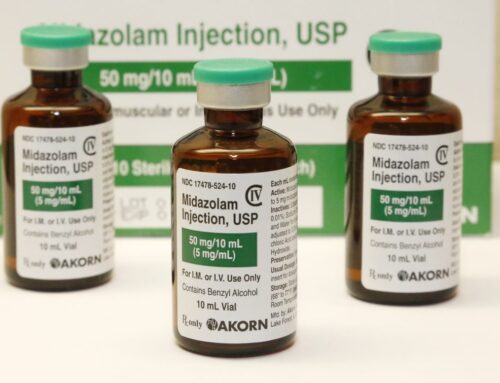

The Tennessean reported in October that the Department of Correction had been waiting, in part, to get the confidentiality law in place before establishing its new lethal injection protocol that uses pentobarbital, common in animal euthanasia.

If the new one-drug protocol had been announced before the law change, it’s conceivable that a citizen might have requested information under the state’s open records act to successfully discover the drug supplier.

Challenges on First Amendment grounds

The question about the public’s access to details about execution drugs has surfaced in Arizona, Missouri and Georgia in state and federal courts as a First Amendment issue.

In a precedent-setting Oct. 7 ruling in Arizona, U.S. District Judge Roslyn Silver took on the state’s argument that it was entitled to keep the source and nature of the drug secret, and ordered the state to make the information public in a case that involved two death row inmates.

She essentially ruled that the state’s reasons for confidentiality were trumped by the First Amendment right of its citizens to have access to information about government proceedings in such a way that allows them to participate in informed debate about public affairs.

She wrote that “…the public must have reliable information about the lethal-injection drugs themselves in order to judge the propriety of the particular means used to carry out an execution.”

After that, the ACLU filed a constitutional challenge in federal court in Missouri when Corrections officials there closed off what had previously been public information on the drug source. It had already filed a lawsuit in Arizona challenging the state’s interpretation of its open records law.

In Missouri, Hustler publisher Larry Flynt also got in the fight in an unsuccessful effort to forestall the execution of the man who shot him in 1978, leaving him partially paralyzed.

Flynt, who has publicly opposed the death penalty, had sought to unseal court records about qualifications of the anesthesiologist involved in the execution, and questioned the state’s actions and ethics trying to keep information from the public.

“I find it totally absurd that a government that forbids killing is allowed to use that same crime as punishment,” Flynt said in a written statement to the Los Angeles Times at the time. “But until the death penalty is abolished, the public has a right to know the details about how the state plans to execute people on its behalf.”

Other arguments follow the same First Amendment claim.

In Georgia, the attorney for a man on death row won an injunction and stay of execution in July after arguments that included First Amendment claims over a new law that conceals the drug source. In that case, the Georgia law goes a step further than laws in Arizona, Missouri and Tennessee with a provision that the information cannot even be accessed through judicial process, said Brian Kammer, executive director of the Georgia Resource Center that has handled the case.

“Here, the attorney general rammed it through,” Kammer said. “There was no evidence supported in his argument that the companies would be harassed.”

Concerned about compounding pharmacies

Many of those challenging the new concealment rules say they are especially concerned that states are now getting the drugs from compounding pharmacies, an industry whose light regulation was exposed last year when contaminated drugs from a Massachusetts compounder caused patient deaths, including in Tennessee.

In Tennessee, no direct challenges have been filed to the law, although requests for the source and nature of the drugs have been made by the federal public defender’s office in Nashville representing death row inmates. Those requests have been denied under the new confidentiality provisions.

The federal public defender’s office has noted in its claims that the only FDA-approved source for pentobarbital is a company whose distribution policies do not allow the drug to be used in executions.

“I think there are real serious questions on where they are getting drugs and what the process was that got them to this (confidentiality) statute,” said federal public defender Kelley Henry. “They get caught breaking the law so what do they do? They pass a statute so we can’t catch them breaking the law.”

It is possible that confidential information about the drug source and the drug may be released at least to the attorneys for the inmates. Last week, Chancellor Claudia Bonnyman signed a protective order that would allow it to be submitted to court under seal.

(Ironically, it was Bonnyman who ruled in 2011 that a drug supplier’s name could not be kept secret under the old law, a ruling upheld on appeal – and the likely trigger to get the law changed.)

But Bonnyman’s order last week does not help the public this time. And the new exemption itself underscores how quickly and easily the government can react with legislation to put what was once public information behind the curtain – in this case it was a Correction Department bill.

Exemptions to the Tennessee Open Records Act now total more than 350 and have been added each year since the act was created in 1957.

TCOG is a 10-year-old nonprofit coalition of media, citizens and good government groups working to preserve and improve transparency in government. Contact Deborah Fisher at [email protected] or (615) 602-4080.