So what ever happened to the fees to inspect bill?

Last year at this time, open government advocates in the state had successfully convinced lawmakers to delay action on an ill-conceived proposal to allow government to charge fees to inspect public records.

Already, the law allows charging citizens fees to get copies of records and the rules have led to out-of-control labor costs with few limits or recourse for citizens and journalists.

The free inspection option is the law’s safety valve, and the last protection for a citizen or journalist who can’t afford the prices and the fights with government officials over costs.

The sponsors of the legislation, who were carrying it at the request of the Tennessee School Boards Association, deferred action in the spring of 2015 and asked the Office of Open Records Counsel, with assistance from the Advisory Committee on Open Government, to study the issues and produce a report.

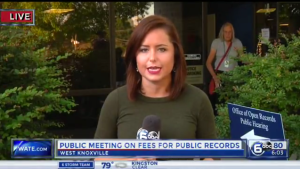

Over the summer, the Open Records Counsel held three public hearings, and conducted an informal survey of citizens and government officials.

The opposition was overwhelming. Each of the hearings drew more people than expected, and almost all spoke against the fees. Journalists, individual citizens, representatives of non-profit and community groups all talked about the need to access records, and not create new roadblocks. Only a few spoke in favor of new fees.

The opposition was overwhelming. Each of the hearings drew more people than expected, and almost all spoke against the fees. Journalists, individual citizens, representatives of non-profit and community groups all talked about the need to access records, and not create new roadblocks. Only a few spoke in favor of new fees.

News coverage captured the sentiment, and later, a Vanderbilt University poll found that 85 percent of Tennesseans thought inspection of public records should remain free.

On Jan. 14, the House sponsor, state Rep. Steve McDaniel, R-Parkers Crossroads, withdrew H.B. 315, killing the legislation. The Senate sponsor, Jim Tracy, R-Shelbyville, said he had no plans to pursue a change in the law either.

On Jan. 15, Open Records Counsel Ann Butterworth produced her report regarding Fees for Inspection of Public Records. It noted that most comments received during the study opposed new fees, and said that the “public’s participation and comments in the surveys and hearings indicate an overwhelming concern, by citizens and government representatives, to maintain, and a desire to increase, transparency of government.”

It also made the following recommendations as potential changes if the costs of preparing records for inspection remain with the governing entity:

Records management:

Provide incentives for best practices.

Adjust/clarify documentation and retention requirements.

Prescribe permitted use of e-mail “in connection with the transaction of official business”.

TPRA (Tennessee Public Records Act):

Make definitions uniform.

Define responsibility within record custodian hierarchy.

Clarify “in connection with the transaction of official business by any governmental agency”.

Provide guidance for custodians when responding to requests that are large and complex or that take more than seven (7) business days for response.

Clarify distinction between discovery requests and TPRA requests.

New legislative initiatives:

Affirm the public need for creation or receipt of additional records/information in light of privacy and security concerns.

Consider cost of records storage, maintenance, and production for inspection.

Anticipate rapid and continuous changes in technology impacting how the records are received, created, and accessed.

Address confidentiality of any information to be created or received, and add a crossreference to Tenn. Code Ann. Section 10-7-504.

No initiatives were undertaken in the just-ended session related to the recommendations. The only legislation directly affecting the process of records requests was by state Rep. Bill Dunn and state Sen. Richard Briggs, both Republicans from Knoxville. Their legislation, which passed and has been signed by the governor, mostly aims to make sure that local public records policies and practices are in line with state law and clear to citizens. It also could make it easier to know how to request a record — for example, each government agency is required by next summer to list the name or title and contact information of a “public records request coordinator” who can be a point person for making sure requests are handled correctly.

It’s doubtful that the fees issues will go away.

Too many citizens and news organizations are getting hit with large bills for copies of records, with per-hour labor costs driven often by an attorney’s rates of $100 to $200 an hour to review the records for redaction. On the other end, some government entities continue to complain about what may be isolated, but still very large requests that take a lot of time to fulfill.

The city of Germantown, for example, recently went public with a resident’s request to see emails to and from the city administrator over two years. According to a story in the Commercial Appeal, the city has said the request covers 36,000 emails, including 22,000 that may contain information that by law is confidential. The city is paying an attorney to scan the emails and redact them.

The attorney has billed the city $46,495 for three months of work. Wow. And they aren’t even done.

The example likely draws various opinions, but also raises several questions:

Was the city helpful to the requester, for example, trying to see if she wanted to first limit emails by search terms?

Did the city offer to fulfill the request in segments, spending a certain amount of time each week on the request?

An obvious one: Instead of hiring an outside lawyer, is there a less expensive way to review and redact?

A most important question we should all be asking: Exactly what is being redacted to begin with? Journalists and others who have received heavily redacted documents are beginning to question and push back on what seems like the Zika virus of public records. In March, The Tennessean was successful in forcing a lawyer for the Sumner County School Board to revisit the heavily redacted monthly bills it produced in response to a records request. The newspaper got a new set of records with less redactions. But they had to pay their lawyer (a good one who is on the board of TCOG!) to do it.

Not everyone has the funds to constantly challenge how government is setting these fees for copies.

Which is why it was so important to maintain the free option for inspection in the law.

What have we learned from all this? I think we’ve learned that what really needs a second look is the state’s Schedule of Reasonable Charges. But this time, perhaps we could view it through the lens of promoting transparency, not diminishing it.