Dispatch call on Elvis death left the building, left a mystery

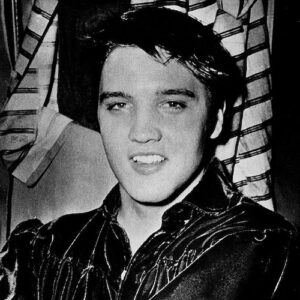

When Elvis Presley was found on the floor at Graceland on Aug. 16, 1977, his road manager called the Memphis Fire Department and an ambulance was dispatched to the scene.

Now, a recording of that call has surfaced at the Tigerman Karate Dojo and Museum in Memphis, advertised as the “fateful 911 call” that “you can hear for the first time ever.” Admission is $24.99.

Why is the recording here, with a private operator, and not in the archives of the Memphis Fire Department?

Person in fire department gave private museum dispatch recording

Billy Stallings said he was given a copy of the recording on a CD at no cost for use in the museum from an individual previously with the fire department, although he won’t reveal who gave it to him.

The dispatch communications of city of Memphis emergency responders to Elvis Presley’s death has emerged in private hands. The recording could be a public record.

It lasts about an hour, he said, and contains police and fire department radio traffic related to the response to the call, including the transport of Elvis’ body to Baptist Hospital. Stallings said he has edited the recording down to about two minutes for museum visitors.

The recording clearly has historical value. And the original recording is most certainly a government record. State law allows for government to retrieve government records that have gone missing.

In Tennessee, the most famous case is the retrieval of an unexecuted marriage license of Davy Crockett that had been taken by a Jefferson County official who had served as the county’s trustee and then, court judge. He gave it to his brother in the 1930s or ‘40s and it ended up in the hands of his niece.

The case went all the way to the Court of Appeals in 2011 because the niece, who lived in Florida, considered the document hers. She said her uncle rescued it when “they were clearing out the courthouse of a lot of papers because of more room and space needed” and her uncle thought his brother “would get a kick out of having this particular piece of paper.”

She even went on the PBS series “Antiques Roadshow” to get her treasure appraised (insurance value, $60,000). According to legend, the marriage license was unexecuted because Crockett was jilted when his fiancee ran off with another man.

As for the Elvis tape, Bill Adelman, the curator of the fire department’s Fire Museum of Memphis, said it’s unlikely that the original reel-to-reel tape still exists.

Dispatch tapes were kept for a year, he said, then erased and re-used unless they were related to a firefighter’s injury, fire death or a significant event.

Adelman, however, said he was given a cassette copy of the Elvis dispatch call in the early 2000s for the purpose of putting it in the fire museum where he then worked. He said he listened to it many times. But his job at the museum was eliminated before he could build the exhibit.

Adelman was rehired two years ago at the museum but said he has lost track of the location of the cassette copy in his home. He said it is his personal copy and he did not give it to Stallings.

Dispatch call may provide new information surrounding Elvis death

Stallings says the recording has interesting content, including Elvis’ road manager, Joe Esposito, calling a second time to the fire department, asking where the ambulance was, emergency responders having to go back to Graceland after the hospital because they left bags there, and Esposito saying someone was not breathing although the call was dispatched as someone having difficulty breathing. Stallings said the call shows it took about seven minutes for the ambulance to get to the home.

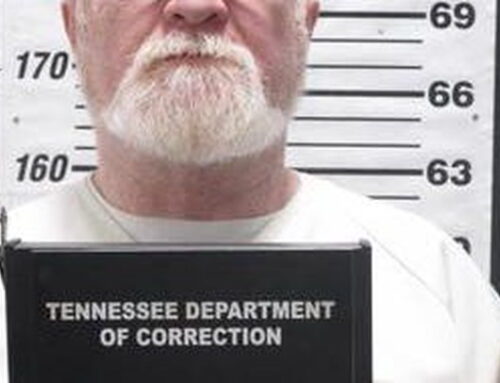

Another person has a recording —Raymond Chiozza, the then-21-year-old fire department dispatcher on the Elvis call who is now the director of the Shelby County Emergency Communications District (911). He said they often made copies of certain dispatch traffic, dubbing snippets onto cassette tapes, such as for training.

He has posted a snippet of his recording on his photography website. It’s very short, about 15 seconds, and doesn’t have the full initial call from Esposito or the second call, which Chiozza said he remembered.

Elvis was dead when emergency responders got to Graceland, maybe dead for hours, but many mistruths were seeded that day.

The medical examiner announced to the press, even before an autopsy was finished and toxicology reports were back, that Elvis’ death was due to “cardiac arrythmia” and drugs played no role.

Later, the public learned that Elvis had been heavily addicted to drugs, aided by a number of personal physicians who liberally prescribed them. Years later, there seems no doubt that drugs played a role.

Would the more comprehensive dispatch communications from that day tell us something we don’t know? Would it add a fact, subtract a piece of misinformation?

I don’t know. I’m not an expert on Elvis. But the recording was a government record that should have been retained for its historical value.

Recording should be available as a public record

Copies of the recording could still be retrieved by government as a government record depending on the circumstances or purpose of the copying.

Davy Crockett’s unexecuted marriage license was returned after an order by the court. It is now in a vault in the Jefferson County Clerk’s office. Occasionally, the clerk’s office said, people will ask to see it. An appointment is made and the now-framed certificate is brought out for examination.

The emergency communications on the Elvis call deserve at least equal treatment. Our government should have an interest in preserving matters of fact — especially in this context — and Memphis government has a unique opportunity and responsibility to save the recording that is part of its city history.