Delaying access to public records violates law, appeals court rules

Government entities cannot ignore the requirement in the Tennessee Public Records Act to provide access to records promptly and still be in compliance with the law, according to an appellate court ruling last week in Jetmore v. Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County.

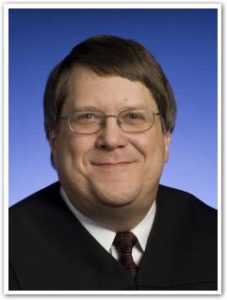

In the opinion delivered by Judge Andy D. Bennett, the court upheld a trial court’s finding against the Metro Nashville Police Department, which had limited the number of traffic accident reports it would provide a requester to three a day.

The appellate court also upheld the award of attorney’s fees to the requester who brought the lawsuit, saying that the police department cannot “insulate itself from a finding of willfulness by adopting policies or relying on advice that is inconsistent with the requirements of the (Tennessee Public Records) Act.”

Metro had argued that it was relying on advice from the Municipal Technical Advisory Service and that it had authority to make “reasonable rules” regarding the making of copies as allowed by T.C.A. 10-7-506(a):

In all cases where any person has the right to inspect any such public records, such person shall have the right to take extracts or make copies thereof, and to make photographs or photostats of the same while such records are in the possession, custody and control of the lawful custodian thereof or such custodian’s authorized deputy; provided, that the lawful custodian of such records shall have the right to adopt and enforce reasonable rules governing the making of such extracts, copies, photographs or photostats.

Metro had argued that it was reasonable to limit a requester to copies of three traffic accidents, and that as long as it provided a response to the requester for additional reports within seven business days, it was within its rights under the law.

The plaintiff, Bradley Jetmore, argued that Metro had in the past provided access to more than three and that the police department was in violation of the Tennessee Public Records Act that says the custodian “shall promptly make available for inspection any public record not specifically exempt from disclosure” unless it is not practicable to do so.

The trial court had agreed, and based on evidence and testimony of how Metro processes traffic reports, recognized that Metro had the ability to produce reports. It found the “three-report” rule was arbitrary and that the city was overlooking the “promptness requirement” in the law. It granted injunctive relief to Jetmore, ordering the city to provide the reports within 72 hours of when the reports are put in the city’s computer system.

In the Oct. 12 ruling, the court wrote that the public records act “permits a records custodian to adopt reasonable rules, but any such rules must fall within the confines of the TPRA.”

“Metro’s form 720 stated that Metro had seven business days to provide copies of public records, and if Metro could not fulfill the request within seven business days, it would let the requestor know when the copies would be available. Metro cited Tenn. Code Ann. 10-7-503(a)(2)(B) on the form as authority for the seven-day period. However the statute gives a custodian up to seven business days to make a record available for inspection only “[i]n the event it is not practicable for the record to be promptly available for inspection.”

“Although Metro followed a practice of promptly providing three or fewer copies of records when a request was made, it systematically refused to satisfy any request for more than three copies while the requestor waited, even if providing more than three copies was practicable at that time. By systematically denying any request for more than three copies of public records at a time, Metro was not complying with the Act’s mandate that records be made available promptly. Only if it is not practicable for a custodian to satisfy a request promptly is the custodian permitted to delay production of the document as set for in Tenn. Code Ann. 10-7-503(a)(2)B(i)-(iii).

Metro had also appealed the lower court’s award of attorney’s fees of about $57,000 to Jetmore, arguing that it could not be found willful because it relied on advice from the Municipal Technical Advisory Service (known as MTAS).

The law permits a court to award attorneys’ fees and costs to a requester in a public records case under the following circumstances:

If the court finds that the governmental entity, or agent thereof, refusing to disclose a record, knew that such record was public and willfully refused to disclose it, such court may, in its discretion, assess all reasonable costs involved in obtaining the record, including reasonable attorneys’ fees, against the nondisclosing governmental entity. In determining whether the action was willful, the court may consider any guidance provided to the records custodian by the office of open records counsel as created in title 8, chapter 4.

In upholding the award of fees, the court referred to the explanation in Taylor v. Town of Lynnville (2017) regarding reliance on advice that is not consistent with the law:

“The default understanding of the statute is that a citizen may inspect public records promptly upon request. Any delayed access to nonexempt public records is contingent only on whether such prompt inspection is practicable… If a municipality denies access to records by invoking a legal position that is not supported by existing law or by a good faith argument for the modification of existing law, the circumstances of the case will likely warrant a finding of willfulness.”

The appellate court also rejected the argument that a “heightened showing of ‘ill will’ or ‘dishonest purpose’ was necessary to establish willfulness, quoting rulings in Friedmann v. Marshall County (2015) and Taylor.

Metro had also argued that the trial court lacked jurisdiction because Jetmore was unable to point to a particular record that he was wrongfully denied.

The appellate court rejected the argument, saying “[w]e note that Metro’s alleged failure to produce the accident reports promptly is tantamount to a denial of the reports in violation of the TPRA.”

“The purpose of the TPRA is to ‘facilitate the public’s access to government records.’.. We believe this purpose would be frustrated if we limited a petitioner’s opportunity to obtain relief under the Act by requiring him or her to specifically identify particular documents to which he or she has been denied, especially if the basis for the petition is the method by which records are (or are not) produced.”

Judge Frank G. Clement Jr. and Judge Richard Dinkins joined the opinion.

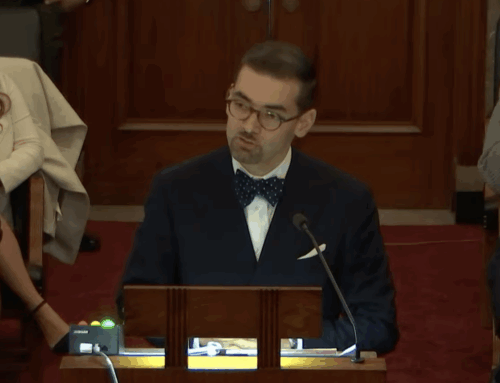

Doug Pierce and Kyle David Watlington represented Jettmore in the appeal. (Pierce is past president of Tennessee Coalition for Open Government).