Government business is not a trade secret

Government officials have found an effective way to keep secrets, especially when they don’t want taxpayers and voters to know about sweetheart deals with favored businesses.

It works something like this.

First, the government officials sign a non-disclosure agreement with the business that says that anything in an upcoming government contract with the business could be considered proprietary, a trade secret or otherwise confidential information of the business, and not disclosable under Tennessee Public Records law.

Next, they agree that they will not disclose anything to members of the public about the deal’s details, even at a public meeting in which a governing body must vote on it.

Often, they agree that any press release or information given out about the government contract must be approved in advance by the company, and that the company has control over what the government says.

Finally, if someone makes a public records request for the documents that outline specific terms, including how much the government is paying or granting, the government will alert the company and allow the company 30 days to object or file to get a court order to prevent disclosure.

Impossible, you say?

Hardly.

Using trade secrets to hide government payments

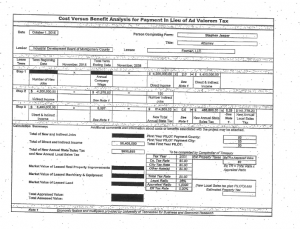

This method started showing up on my radar more than a year ago, when requests for the government’s Payment-in-Lieu-of-Taxes (PILOT) agreement with Google in Montgomery County were stonewalled, and the paperwork eventually released had key monetary information about the government’s grant of land redacted.

The same concepts have been used to hide the fees that public colleges are paying to investment firms to manage endowments.

Here’s a sample of what the chairman of the Montgomery County Industrial Development Board signed in 2015:

“…the Board understands and agrees, that any and all information contained in this (PILOT) Agreement, and/or any related agreement, exhibit, schedule or other writing in whatsoever way related to the project, including, without limitation, the number of employees projected to be hired or actually hired to operate the Project, capital investment by the Company in the Project, the relative proportion or real versus personal property invested…and the assessed value of either real or personal property as a component of the total assessed value of the Project, are…considered to be ‘trade secrets’…”

Similar language has shown up in a Volkswagen agreement in Chattanooga, where the company has received Tennessee’s largest local and state incentive package to date, now more than $1 billion.

“…each Public Authority hereby agrees to redact any information in this Agreement which the Company deems, in its sole and absolute discretion, proprietary,” says the local government contract with Volkswagen in Chattanooga, signed by the city and county mayors.

Getting around the Open Meetings Act

For those who might think transparency is preserved because industrial development boards are subject to the Open Meetings Act and must vote on contracts in public, consider this language in the Google contract:

“The Board agrees that it shall not attach a copy of this Agreement to any public notice or present this Agreement for review in any public forum or provide a copy or disclose the terms or conditions of this Agreement to any third party, except” when required by law or ordered by the court to do so.

And if someone does try to get a court order to release information in the contract, the Board agrees “to use its best efforts legally permissible in order to assist the Company in opposing the issuance of such order.”

The Public Records Act assures that the public has a right to know about government business. It defines public records as any document made or received in connection with transaction of official government business.

Entering into economic development contracts that exempt a company from paying property taxes and allows them to operate on property assembled by the government using taxpayer money is clearly a transaction of government business.

So is paying an investment manager to manage public funds.

Government business should remain public business

That is why we are supporting a bill in the legislature that would make certain the payments made by government to a private entity cannot be made confidential under the trade secrets law.

This method of ceding authority over government records to a business — allowing the business to call the shots over which government contracts and payments are confidential and which can be shared — is an insidious assault on the Tennessee Public Records Act and the public’s right to know.

Government business should remain public business.

Deborah Fisher is executive director of Tennessee Coalition for Open Government.