Appellate court reverses trial court, upholds attorney fee provision in public records case

The Court of Appeals on Thursday found a Lynnville city recorder was willful in denying a citizen access to inspect public records when she required an upfront $150, and remanded the case back to consider the award of the citizen’s attorney fees.

It is the third case in two years in which the appellate court has said that a wrongful denial of public records must be based on law or a good faith argument about the law to avoid the award of attorney fees.

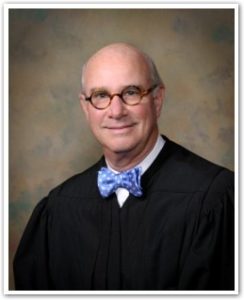

In the opinion delivered by Judge Arnold B. Goldin and joined by Judge J. Steve Stafford, the court reversed the trial court’s ruling that did not find the town of Lynnville willful in denying records to citizen Rickey Joe Taylor. Without a willful finding, citizens wrongfully denied access to records cannot be eligible for their attorney fees to be reimbursed, though they had to sue to gain access.

In addition to remanding the case back to the trial court to consider attorney fees to Taylor at the trial court level, it also ordered that costs and attorney’s fees incurred in the appeal be awarded to Taylor.

Read the appellate court’s decision.

Taylor made three separate requests to inspect Lynnville public records in December 2015 and January 2016. The records sought included minutes from town board meetings among other things. But the city recorder, Amanda Gibson, said that Taylor would have to pay $150 up front before he could see those records.

The law only allows a government entity to impose charges when a citizen requests copies of public records. If someone merely wants to inspect records, as Taylor did, no fees can be assessed. The court wrote:

“Inasmuch as charges for the inspection of public records are generally prohibited, Mr. Taylor’s right of access should not have been conditioned on the payment of an upfront fee. In our view, the imposition of an impermissible condition on a record’s availability constitutes a denial of a request for that record under the TPRA.”

The court also ruled that the denial of the second and third requests were willful under the law, and thus triggered the ability for the citizen to have attorney’s fees awarded in the discretion of the trial court judge.

“Having considered the nature of the Town’s responses to Mr. Taylor’s second and third requests, we conclude that the Town’s effective denial of access was willful inasmuch as it erected several barriers to access that had no basis in law….As we have already noted, “[a] records custodian may not … assess a charge to view a public record unless otherwise required by law[.] Tenn. Code Ann. 10-7-503(a)(7)(A). It is simply wrong to insist on the payment of an upfront fee to gain rights of access to inspect the requested public records.”

The ruling devotes several paragraphs to defining the “appropriate framework for the analysis that is to be employed when determining whether a government’s denial of records was willful.” It referred to its previous opinions in Friedmann v. Marshall County and Clarke v. City of Memphis, both in 2015.

“In summary, we noted that ‘[i]f a municipality denies access to records by invoking a legal position that is not supported by existing law or by a good faith argument for the modification of existing law, the circumstances of the case will likely warrant a finding of willfulness.’ “

Before these opinions, some lower courts had considered willfulness to require a showing of “ill will” or “dishonest purposes,” which the appellate court has rejected.

The standards for determining willfulness is important because state law only allows a judge to award attorney’s fees to the citizen who was wrongfully denied access to public records if it finds “that the governmental entity, or agent thereof, refusing to disclose a record, knew that such record was public and willfully refused to disclose it.” [T.C.A. 10-7-505(g)]

One unusual aspect of this case was the availability of a video that recorded Taylor’s interaction with the city recorder on his third request when he appeared in town hall to request the records in person.

In that video recording, Taylor asks to view the records and Gibson tells him she is “really busy” and tells him he can come back to inspect the records later that afternoon. When Taylor returns in the afternoon, Gibson said she will not allow Taylor to view the records and that she had tried to contact the city attorney. She tells him that he can view the records the next Friday only if he pays the $150 fee.

In a trial court hearing, Gibson said she did not let Taylor see the records on his return visit “[b]ecause I could not get ahold of the city attorney.”

The town argued that Gibson was not willful because she was following advice from the city attorney.

But the appellate court said, with boldface added:

“In our opinion, it matters not that a records custodian sought out legal advice if the legal position adopted by the records custodian is without any basis in the law or a good faith argument for a modification of the law. After all, governmental entities are themselves charged with fostering access to public records under the TPRA. When a governmental entity is confronted with a public records request, it assumes ultimate responsibility for a faithful and legal administration of the TPRA. Indeed a governmental entity ‘cannot remain unknowledgeable of the [TPRA] and authority interpreting it and thereby immunize itself from liability for attorneys fees…’ Although deference to counsel may certainly be advisable, we are of the opinion that such deference does not countenance against a finding of willfulness in situations where there is no good faith legal argument for the denial of access.”

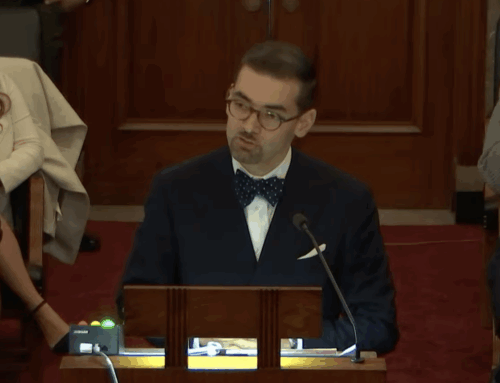

Judge Brandon O. Gibson wrote a separate opinion in which she concurred, but expressed concern that the General Assembly’s may have intended to allow a governmental entity to charge for labor even if copies are not requested, and quoted an earlier version of the statute.

But in the majority opinion, the appellate court said

“[W]e are unconvinced that the prior version of the statute clearly reflected the intent suggested by Judge Gibson…As it is, the existing provisions of the TPRA clearly tie the assessment of labor charges to a request for copies of public records. Although Judge Gibson appears to question the wisdom of this policy choice, we do not share the same concerns. In our view, the General Assembly has enacted a measured approach that is consistent with the purpose of the TPRA. The TPRA plays ‘a crucial role in promoting accountability in government through public oversight of governmental activities’ Memphis Publi’ng Co., 87 S.W. 3d at 74 (citation omitted), and it is ‘to be broadly construed so as to give the fullest possible public access to public records.’ Arnold v. City of Chattanooga, 19 S.W.3d 779, 786 (Tenn. Ct. App. 1999) (citation omitted).

“Access is important, and there is no question that the requirement of the payment of money merely to inspect public records could serve as a barrier to access. As such, we are not troubled that the TPRA only allows for the assessment of labor charges in specified circumstances. Any such requirement for the payment of money that could accompany a request merely to view records could only serve as a deterrent to public access and governmental accountability.”

Taylor was represented in the case by attorneys Robert Dalton and David Hudson.