Appeals Court: Records in Memphis police chief search not public

The Court of Appeals ruled this week that applications sent to a police association charged with interviewing and identifying finalists for a new Memphis police chief last year do not have to be released under the state’s public records law.

The International Association of Chiefs of Police was contracted by the city of Memphis for $40,000 to conduct a search for a new director of police, identify and interview semifinalists and “recommend a group (approximately six) of the most highly qualified candidates for further on-site evaluation.”

Last summer, a reporter with The Commercial Appeal requested to see all applications, noting he was “primarily interested in the finalists,” but the city and the IACP denied the request. IACP is a non-profit professional association of more than 25,000 law enforcement officers, and is headquartered in Virginia.

The Commercial Appeal filed a petition with the court to gain access. Shelby County Chancellor Walter Evans ruled that the records were subject to public inspection because the IACP acted as the functional equivalent of the city in recruiting a chief, and, alternatively, because the position of police director was the same as a “chief public administrative officer” specifically identified in the public records statute for which employment applications are mandated to be open.

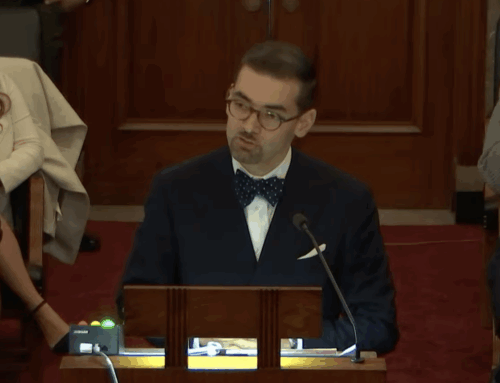

In an opinion delivered by Judge Richard Dinkins, the Court of Appeals reversed the chancery court’s decision, reasoning that the nonprofit association’s contracted work to receive all applications and identify finalists for the position of police chief was not a government function. Dinkins also wrote that although “chief public administrative officer” was not defined in the statute [T.C.A. 10-7-503(f)], it was meant to apply to city managers not directors of police departments.

As the public records act relates to private entities doing government work, the Tennessee Supreme Court in 2002 adopted a “functional equivalent” framework in Memphis Publishing Co. v. Cherokee to determine “whether a non-profit corporation that provides privatized services to a governmental entity is subject to the public access requirements of the Tennessee Public Records Act.”

In Cherokee, the Tennessee Supreme Court ruled that a private nonprofit that provided child care services was subject to the public records act, and said, “[w]hen a private entity’s relationship with the government is so extensive that the entity serves as the functional equivalent of a governmental agency, the accountability created by public oversight should be preserved.”

Dinkins, in his opinion joined by Judges Arnold B. Goldin and Kenny W. Armstrong, said “we have determined that the services performed by IACP in identifying potential candidates for the position of Director of the Memphis Police Department does not equate to performing a government function. The governmental function here is the hiring of the director of police, and this function was never delegated or assigned to the IACP… (we) do not construe the essentially administrative tasks of conducting a preliminary search and delivering a non-binding list of recommended candidates to be the same as managing a program of the City or otherwise making a decisions that would bind the City. Rather the services IACP performed were incidental to the selection of the director…”

Read the opinion Memphis Publishing Co. v. City of Memphis

The court also considered the level of funding of IACP, noting that the $40,000 fee was less than 1 percent of IACP’s annual revenue, and that the city did not exert control or regulation over IACP, both of which are tests in the court’s functional equivalent analysis. Finally, the court said IACP was not created by the Legislature nor was its records previously determined to be open to public access.

The court also reviewed a part of the Tennessee Public Records Act mandating disclosure of applications:

T.C.A. 10-7-503(f): All records, employment applications, credentials and similar documents obtained by any person in conjunction with an employment search for a director of schools or any chief public administrative officer shall at all times, during business hours, be open for personal inspection by any citizen of Tennessee, and those in charge of such records shall not refuse such right of inspection to any citizen, unless otherwise provided by state law…

IACP and the city had argued that the trial court’s holding was in error because the statute did not apply to the position of director of police. The newspaper, however, relied on a previous court ruling and a 2016 Attorney General opinion in contending the records should be public.

Dinkins wrote that if the General Assembly had wanted “chief public administrative officer” to apply to police chiefs, it could have specifically included “chief law enforcement officer” in the statute.

The Commercial Appeal’s editor Mark Russell said the newspaper has not yet decided whether it will pursue an appeal before the Tennessee Supreme Court.

The mayor’s office released the names of six finalists on July 15, 2016, and a new police chief was named in August 2016. The city decided to promoted deputy police chief Mike Rallings to the job, replacing Toney Armstrong.