This story about the Vanderbilt rape case, written by Tony Gonzalez, was published by The Tennessean on March 12, 2014 and reprinted here with permission.

Some records in a high-profile Vanderbilt University rape case should be made available under the Public Records Act, a Davidson County Chancery Court judge ruled Wednesday in response to The Tennessean’s lawsuit against Metro government over access to information.

In an 18-page order, Chancellor Russell Perkins ruled that some text messages, emails by witnesses and defendants, and other records given to police by the university were public documents and should be given to a media coalition that sued for access.

But those records won’t immediately be provided to the media coalition. Perkins put a stay on his own order, pending an anticipated Metro appeal or other possible court action.

The Tennessean led a statewide coalition of news organizations including the Associated Press, Knoxville News Sentinel, Chattanooga Times Free Press, the Commercial Appeal in Memphis and several television stations that sued Metro last month over its refusal to release third-party records from the rape investigation, which led to charges against four former Vanderbilt football players.

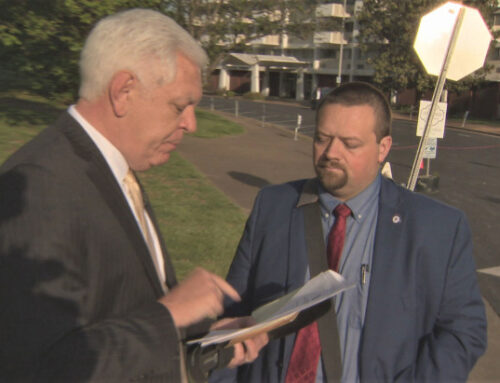

“We are delighted with the chancellor’s thorough treatment of the public records analysis and we hope to obtain access as quickly as possible,” said Tennessean attorney Robb Harvey of Waller.

Maria De Varenne, Tennessean editor and director of news, said it is “important for us as watchdogs for the public to look into and shed light on how the government, including the police and the DA’s office, handled this significant case involving Vanderbilt and its football program.”

The lawsuit said records created by nongovernmental entities and obtained by the Metro Police Department since the June 23 incident, including text messages between players and coaches, should be available for public inspection.

A Metro government attorney argued that case law says open investigative files are not public records.

Perkins reviewed six binders and more than 70 CDs and DVDs of case information — including police interview recordings with former Vanderbilt coaches James Franklin and Herb Hand, both of whom left to work at Penn State University.

The judge wrote that text messages — but not photos and videos of the alleged sexual assault — are public records and that they do not expose the investigative tactics of police. The media coalition repeatedly has said it does not want to identify the victim or get access to photos or videos of her taken during the alleged crime.

He ruled that Vanderbilt access card information and campus video data, as well as emails written by potential witnesses and defendants are public, provided those messages were not addressed to police or the district attorney’s office.

“What happened in that dormitory and any examination of the conduct of Vanderbilt students and employees regarding the incident in question are newsworthy,” Perkins wrote, “but the Court’s review of the records and of the text messages shed very little light on official government conduct.”

Perkins deferred ruling on questions of the defendants’ rights to fair trial and the alleged victim’s right to privacy, saying that the Davidson County Criminal Court, where the former football players will stand trial, would be the proper court for that discussion. Metro and the state attorney general’s office had argued to be heard there.

Metro Legal Director Saul Solomon praised the ruling for deferring to the criminal court.

“We’ve said all along that the criminal court is in the best position to make a decision on what should or should not be disclosed to the public before the jury gets to see it,” he said.

Solomon said Metro hasn’t decided what to do next. By his reading of the order, the finding that some records are public doesn’t mean they’ll be disclosed, because the interests of fair trial and victim privacy remain unanswered, he said.

NOTE: Tennessee Coalition for Open Government is part of the coalition that brought the lawsuit.