In 2005, then-Gov. Phil Bredesen was planning a major scaleback to TennCare to, as he put it, “save” the program whose costs were rising exponentially.

A sit-in was staged at the Tennessee State Capitol over several days to protest, to no avail.

Karl Davidson, who was among the protesters, later alleged in a lawsuit that he and others at the sit-in were willfully and maliciously harassed and intimidated by various state officials and highway patrol officers in retaliation for exercising a protected First Amendment right. Further, he said this harassment was done at the direction or at least knowledge of the governor and deputy governor.

His claims of constitutional violations ultimately failed, but it was within this case that a potentially troubling court precedent was established regarding the deliberative process privilege.

Development of deliberative process privilege

During the case, Davidson asked for a series of documents, mostly notes from meetings and telephone conversations among the governor’s legal counsel and with the attorney general’s office, and notes and edits by the attorneys on a document concerning the use of public areas around the State Capitol.

The Court of Appeals in an opinion authored by Judge Richard Dinkins ruled that the deliberative process privilege protected the documents sought by Davidson and he could not get them. (Davidson v. Bredesen, 2013).

The Court of Appeals had said “there is a ‘valid need’ that the advice high governmental officials receive be protected from disclosure.”

“The officials who are able to claim the privilege are those vested with the responsibility of developing and implementing law and public policy, many times requiring that differing and various interests and viewpoints be considered. In this context, the privilege recognizes the official’s relationship with trusted advisors as a relationship which is fundamental to the process of deliberating toward the result and which is sufficiently important to justify a limitation on the ‘need to develop all relevant facts in the adversary system [which] is both fundamental and comprehensive.’ “

The court had concluded that the “deliberative process privilege” outweighed Davidson’s rights of get the information in the court case.

Open government advocates were alarmed at the decision to use the “deliberate process privilege” to shield the documents. Attorney-client privilege or work product protection could have been sufficient for at least some of the documents. And they worried that the court’s broadly worded ruling could spur public officials to begin claiming confidentiality of documents and reports that traditionally have been considered public record.

“It is no stretch of the imagination to envision a city or county mayor refusing to release a traffic study about a dangerous intersection or a negative feasibility study about a pet public project, claiming that the documents were used to formulate policy,” wrote the Knoxville News Sentinel in an editorial.

Gov. Lee refuses to release department recommendations

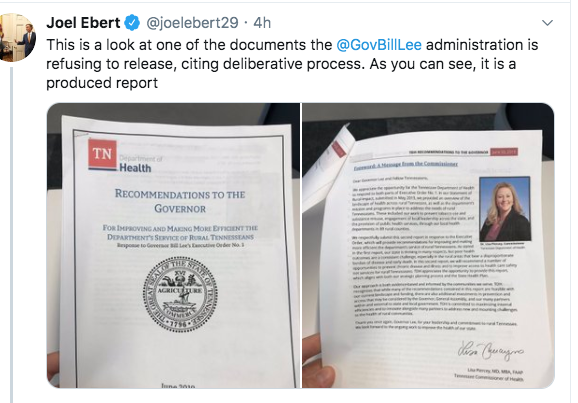

This week, The Tennessean reported that Gov. Bill Lee’s administration is refusing to release recommendations of the departments in the executive branch for improving their services to rural Tennesseans.

Lee had requested the recommendations in his very first executive order, in which he also asked for assessments of each department’s activities and impact in rural communities. The governor’s office released the assessments, but cited the deliberative process privilege in refusing a public records request for the recommendations.

The governor’s spokeswoman Laine Arnold explained that the recommendations are not established policies of the administration.

“Drawing conclusions about policy ideas from an incomplete document at a single department would be like calling the ballgame after watching only one team in warmups,” she told The Tennessean.

In Davidson, the court had concluded that the “deliberative process privilege” trumped Davidson’s rights to information that he thought could help prove his court case.

An earlier Court of Appeals in Swift v. Campbell (2004) had also recognized deliberate process privilege, but declined to apply it to an assistant district attorney general. The court expressed caution:

“Protecting the confidentiality of conversations and deliberations among high government officials ensures frank and open discussion and, therefore, more efficient government operations. … However, the deliberative process privilege must be applied cautiously because it could become the exception that swallows up the rule favoring governmental openness and accountability. If governmental employees at any level could claim the privilege, Tennessee’s public records statutes and open meetings law would become little more than empty shells.

“Whether the ‘deliberative process privilege’ may be invoked depends on the governmental official or officials involved. We have no doubt, for example, that the Governor may properly invoke this privilege, should he or she care to, in meetings with staff or cabinet members. We have also held that the Constitution of Tennessee embodies a version of the privilege for the General Assembly when it decides to invoke it.”

Should agency recommendations be exempt?

Whether or not written recommendations by state agencies to the governor’s office about improving state services in rural areas are exempt from disclosure under the Tennessee Public Records Act is a legal question. Whether such recommendations should be exempt from the public records act is a question worth all of our reflection in light of the law “favoring governmental openness and accountability.”

Would any report with a recommendation to the governor, prepared by a government agency, or its commissioner, be confidential? Do such recommendations only become public when and if the recommendations are incorporated into the governor’s own plan? Would members of the General Assembly have access to the recommendations of state agencies, regardless of whether they were adopted by the governor as his policy?

Are the reports the products of the commissioners personally, or of the agencies they oversee — agencies that traditionally produce reports and recommendations that are public? Do the written recommendations in response to an Executive Order fall into the category of communications with the governor that must be kept confidential to ensure “frank and open discussion”?

Does keeping such recommendations under wraps serve the purpose of better informing Tennesseans of the debates and policy issues that must be decided by their representatives?

And finally, would commissioners who authored or signed off on the recommendations be prohibited from sharing their thoughts with the public at large? Is it the sort of sensitive advice that needs to be confidential?

The Tennessean obtained the Department of Health’s recommendations, but didn’t say how they got the report. The 21 other recommendation reports appear to remain under wraps, unless others are leaked to the press.

The government policies addressing problems in rural parts of the state is of interest to a number of citizens.

If one believes in the marketplace of ideas, as I do, making public policy recommendations from state agencies on issues as broadly important as rural improvement can only strengthen the end result.