By Deborah Fisher

Executive Director of Tennessee Coalition for Open Government

When government officials get into the business of economic development, they usually face the choice between transparency and secrecy.

Too often, they choose secrecy. And sometimes the law allows it.

At the state level, specific exemptions to the Tennessee Public Records Act give the state’s Department of Economic and Community Development broad latitude to keep confidential who they are talking with and incentives they are offering.

Only after a deal is done, and the state has signed on the dotted line about how much money it has agreed to give a company in exchange for jobs, can the public find out about it.

That rubs some citizens and advocates for open government the wrong way, and has been fodder for news stories, especially when details are leaked or suspicions arise involving politics, fairness or special interests.

You can follow those threads in recent stories about Volkswagen plant incentives. You can also find it involving the previous administration’s deal to bring Electrolux to Memphis.

Local economic development boards

Despite this cloak around giving and getting state economic incentives, not all of our laws are written to shield such decision-making.

In fact, one particular statute makes clear that county-level economic development boards are subject to the Open Meetings Act: Tenn. Code 6-58-114.

This part of the law instructs each county to establish a “joint economic and community development board” the purpose of which is to “foster communication relative to economic and community development between and among governmental entities, industry, and private citizens.”

It goes on to say that each board must meet four times annually, minutes of all meetings must be recorded, and the meetings, including of its executive committee, are subject to the open meetings law.

A city or county has to certify its compliance with this part of the law if it wants to apply for any state grant, such as a community development grant.

Because of the open meetings requirement, citizens can have potentially more knowledge at the local level and potentially more say in how things get done than they can at the state level.

But you can’t deny the allure of secrecy. And local officials have sometimes gotten crosswise.

Citizens allege Open Meetings violations

A lawsuit in Greene County over the construction of a plant to make liquid ammonium nitrate (a component in industrial explosives) centers upon the secrecy around bringing it to town. (Read Greeneville Sun story about the lawsuit: Group files suit against county for rezoning on plant)

Environmentalists have fought hard since US Nitrogen’s plans came to light, concerned about the Nolichucky River and air quality.

In February 2011, some neighboring property owners protested vigorously at the Greene County Planning Commission meeting where commissioners voted to change the zoning for nearly 400 acres from “General Agricultural” and “Industrial” to “Heavy Impact Use” for use by a new industry without disclosing the company or what it wanted to build.

The lawsuit alleges specifically that the planning commission violated the Open Meetings Act by withholding information about the company and not giving adequate notice “of matters of significant public interest material to the rezoning application…”

Now attention has turned to the Greene County Partnership, which presented the zoning change to the Planning Commission, allowing the company to remain anonymous.

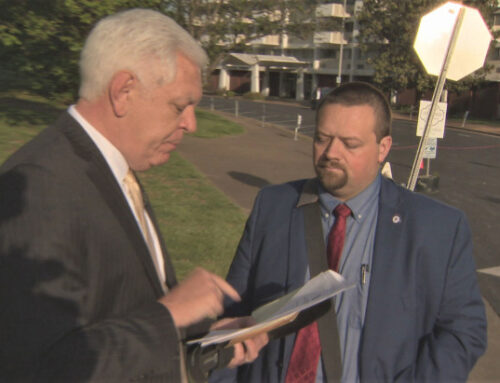

Herbert Moncier, a Knoxville attorney, represents citizens who allege the Open Meetings Act and their constitutional rights were violated because of how government kept secret US Nitrogen’s plans.

The citizens’ lawyer, Herbert Moncier of Knoxville, has presented documents to the court that show the county had asked for the Partnership to be recognized as its economic development board as early as 2001 to fulfill the state’s requirement when applying for state grants.

Such an organization is subject to the Tennessee Open Meetings Act.

The county attorney argued the Partnership was not the county’s economic development board and tried, unsuccessfully, to get them dismissed from the case.

All of this regarding economic development boards has come up before, next door in Unicoi County.

In 2003, the Tennessee Attorney General was asked if the Economic Development Board of Unicoi County was subject to the Open Meetings Act. The AG said no in its first opinion. But two months later revised that opinion and said that new documents showed the board had agreed to operate under the Sunshine Law because it had been used to satisfy the requirements of Tenn. Code 6-58-114.

Proposed bills out of Memphis for four years have sought to shield economic development efforts from the open records law. So far, they have gone nowhere.

Deborah Fisher can be reached at [email protected] or (615) 602-4080. She writes regularly about open government issues.