In what may be the first legal challenge to government delays on public records requests in Tennessee under a 2008 law, a judge has ruled that Metro Nashville violated the “prompt” provision in the statute by holding up traffic accident reports.

Senior Judge Robert E. Lee Davies ordered the city to provide access to the reports within 72 hours of their creation.

He also found that Metro Nashville Police Department’s request form did not comply with the Public Records Act because it stated that the city had “seven business days to process” a records request, which is contrary to law.

Many requesters, including journalists across the state, often complain that government entities slow-walk their public records requests even when the record they seek is readily available. In late 2014, for example, the Metropolitan Development and Housing Agency in Nashville initially refused to release a document that had been voted upon a few days earlier by a subcommittee of the public agency’s board of directors. The public information officer told the news reporter she had seven business days to release it, which would been after the full board voted on the document.

But the law says differently, which Judge Davies recognized in his order signed last week. The statute states:

“The custodian of a public record or the custodian’s designee shall promptly make available for inspection any public record not specifically exempt from disclosure. In the event it is not practicable for the record to be promptly available for inspection, the custodian shall, within seven (7) business days:

- Make the information available to the requester;

- Deny the request in writing, or by completing a records request response form developed by the office of open records counsel. The response shall include the basis for the denial; or

- Furnish the requester a completed records request response form developed by the office of open records counsel stating the time reasonably necessary to produce the record or information.”

Davies noted that “(w)hether a governmental entity is acting ‘promptly’ under the statute will have to be determined on a case by case basis.” But he said the proof in the case provided by Metro on its processing of traffic accident reports “establishes these reports should be available for public inspection after seventy-two hours from the end of the shift of the investigating officer. This proof in consistent with Metro’s procedure over the last two decades…”

“There is no question Metro is able to produce the vast majority of these accident reports for inspection well before the expiration of seven days from the date of the accident,” he wrote.

Providing public records promptly

The provision about providing public records promptly was added to the law in 2008 after recommendations from the Joint Study Committee on Open Government.

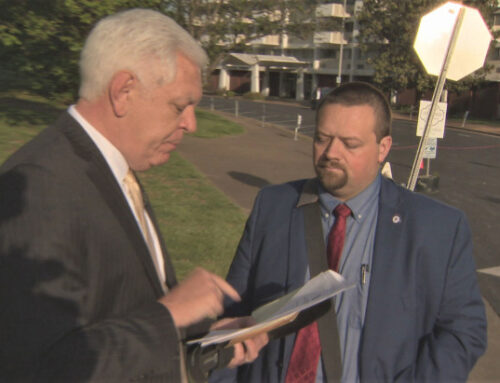

“As far as I know, this is the first time in Tennessee anyone has challenged the ‘promptness’ for producing records,” said Doug Pierce, attorney for the requesters. “(The city) took it upon themselves to mean they didn’t have to do anything for seven days.”

Pierce also is a member of Tennessee Coalition for Open Government’s Board of Directors. The claim of getting to delay records for seven days no matter what they are is a position commonly taken by public records custodians across the state, despite the fact that it’s contrary to the law. To enforce the law, a requester has to file a lawsuit.

This case arose after the police department’s records division ended a more than 20-year practice of making copies of traffic accident reports within about three days and delivering them to the North Precinct where anyone could inspect, and get copies for those they wished to purchase.

Beginning in the fall of 2015, Metro limited the number of copies someone could get on the same day to three. It also began delaying the process so that accident reports available were about three weeks old.

The reports are often sought for commercial purposes, as they were in this case.

In addition to ordering the police department to end the delays, the judge said Metro’s policy of providing only three records upon request was arbitrary and “contradicted by the proof in this case of Metro’s ability to produce copies of multiple accident reports within seventy-two hours of the end of the shift of the investigating officer.”

Pierce said his clients also had trouble getting the division to completely fulfill their requests. He said they would make a request for several traffic reports, get three of them right away, and then within seven days, more. But multiple times, the rest of the reports were never provided and no explanation was given.

“They put the onus on the requesters – that’s all they were going to give you unless you went back and said, hey, what about my other 40?”

In his ruling, Davies noted the question of whether the “prompt” statute applies to a request for copies, in addition to the ability to simply inspect the record.

“The Court finds that it does. Although this portion of the statues does not specifically address copies, as a practical matter, once an accident report has been produced for inspection, a requestor should be able to obtain a copy of that record promptly from the Central Records Division of Metro.

“… Moreover this interpretation complies with the directive of the Legislature to broadly construe the Public Records Act ‘so as to give the fullest possible public access to public records’ . T.C.A. § 10-7-505 (d).”

Davies ordered Nashville to amend its police department form, and said if it is unable to promptly produce requested accident report, it should within seven business days send a written notification telling the requester when they will be available.

The city of Nashville, upon receiving the judge’s order, promptly filed a notice to appeal.