Just how transparent is the state of Tennessee with its economic development programs?

In the eyes of Tennesseans, not very.

A new poll by icitizen and The Beacon Center of Tennessee measured opinions about the state’s economic development activities. The Beacon Center favors stemming “corporate handouts” to specific companies in favor of lowering business taxes for everyone. Most of the questions were designed to measure approval or disapproval of incentive programs.

While the poll results show mixed opinions about tax breaks for select companies, what’s indisputable is that Tennesseans largely think the state is not transparent about them.

A whopping 72 percent agreed with the statement: “State government is not transparent with the incentives it provides to corporations.”

That’s not a number to ignore. When people think government is done in secret, they tend to get suspicious of what government is doing. Considering the importance of a good economy to Tennessee’s well-being and future, could steps be taken to improve understanding of the state’s programs run through the departments of Economic and Community Development and Revenue?

And even better, would increased transparency give citizens and policy-makers better information on which to make better decisions?

Occasionally, we see lawmakers question the amount of secrecy involved in giving taxpayer money to companies. In a Senate Finance Committee meeting in March, for example, lawmakers were asked to approve a $30 million earmark for a company without knowing who it was, where it was or what the company would be doing.

State Finance Commissioner Larry Martin would only describe the project as “exciting.” State Sen. Bill Ketron, R-Murfreesboro, pushed back, noting past projects that fell flat. He said he was uncomfortable voting on the basis of state officials saying, “Trust me, it’s going to be good.”

Still, lawmakers approved the money. State Sen. Lee Harris, D-Memphis, noted in an opinion column later, “Bizarrely, the fact that this juicy, little secret was in the budget, which wouldn’t be revealed to the public or lawmakers, seemed to be point of pride at budget hearings.”

The law allows state government to keep secret economic development packages until after the deal is signed. News reporters cannot use the Tennessee Public Records Act to find out a proposed financial package to a company — no matter how significant or large — and lawmakers are equally impotent.

The reasoning is that if Tennessee negotiators revealed how much they were offering companies, another state would use that information to increase its offer and Tennessee could lose the deal. I’ve never fully bought into that argument because it’s hard for me to believe that a company would 1) walk away from a great incentive package in Tennessee if that’s the place they want to be and all the other factors are right, and 2) refrain from sharing the amount of a Tennessee offer with another state if the factors were better there. The secrecy seems to benefit only the company, not the state.

However, that’s only one part of the transparency puzzle.

The other part, and I believe the more important part, is the ability of citizens and lawmakers to measure and understand the effectiveness of programs.

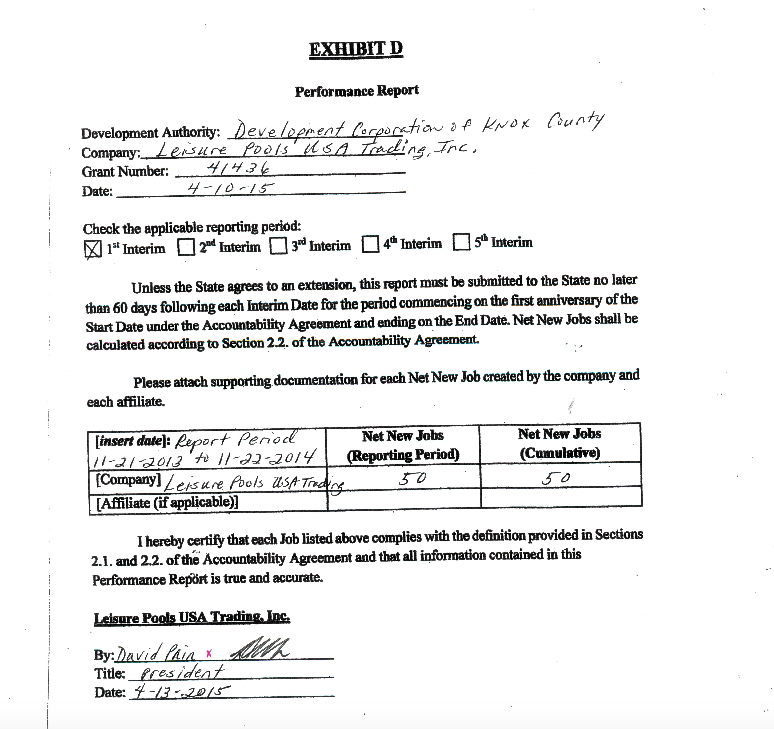

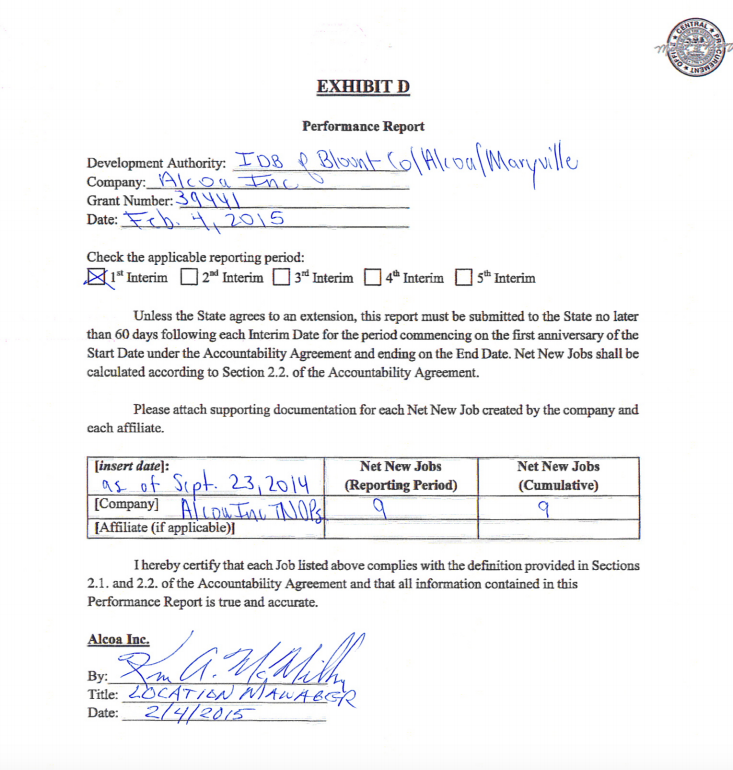

To its credit, the Tennessee Department of Economic and Community Development has a website called, Open ECD. On this website, you can look at lists of companies who have received grants and the amounts. You can also look at PDFs of reports submitted by companies on how many jobs have been created. You can even sign up for email alerts when documents are added to website.

But the website, however well-intended, is woefully horrible in providing any information that allows people to understand the effectiveness of programs.

An example of a Performance Report on job creation by a FastTrack grant recipient, from the Open ECD website.

For example, the PDFs of company reports on jobs do not have information about the grant amount, nor how many jobs were supposed to be created. While that information may exist somewhere, it’s not linked.

The state has touted that it writes “clawback” provisions into contracts. But there is no information on the clawback provisions for each company’s grant, and no information on the website about when or if the state has ever even used a clawback. Are we to assume that in Tennessee all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the businesses who get grants always live up to expectations?

All this disconnected, impenetrable information on OpenECD is still only part of the transparency puzzle.

The state’s economic development programs encompass many different types of incentives that can basically be broken down into two areas: grants (cash), and tax credits (which offset a company’s tax bill).

While some information about grants is publicly available, information about tax credits is not.

Because of rules protecting taxpayer information, the state Revenue Department which handles the credits cannot or will not reveal the value of the various credits used each year by businesses in Tennessee.

The executive director of the Fiscal Review Committee reported a key problem with this secrecy in a report in December: Lawmakers who propose legislation for new tax credits rely on committee staff to calculate estimates, known as “fiscal notes,” on how much the credits will cost in tax revenue. But the Fiscal Review Committee has no way to check whether its estimates are on target because the state revenue department will not give them any information about the use of the credits. In other words, the fiscal impact of tax legislation on the state’s budget is confidential, so lawmakers have to make decisions about tax policy in the complete dark, without any data.

This was also an issue when the Haslam administration refused to release a tax collection study that was used to support the rewrite of parts of the tax code for business last year. The study, the administration said, supported the need to change the tax code in the way the administration wanted it changed, but no one was allowed to actually see the study. (A tax accountant sued on behalf of one of his clients to get the study, arguing essentially that the state’s interpretation of the public records exemption did not make sense, but he lost at the trial level and on appeal.)

One small piece of good news is that state and local government must begin reporting in their financial filings how much revenue they lose in certain tax breaks because of a rule change from the national General Accounting Standards Board. The rule goes into effect for budgets that started in December, so the information on the cost of these tax breaks is expected to start showing up in 2017 reports.

Advocates did not think the rule went far enough, leaving out some categories of tax breaks, but it will open the door to some information.

Meanwhile, Tennessee has not been eager to require companies to provide information related to job creation in exchange for giving them money.

The last legislation passed by the General Assembly was in 2014. It required recipients of FastTrack grants or loans to report annually to the Department of Economic and Community Development the number of net new jobs produced, the cumulative amount of net new jobs during the entire grant period and amount of the grant. But requirements that companies disclose whether the jobs are full-time, part-time or temporary, and by wage group, was stripped from the final bill. The bill was sponsored by Sen. Lowe Finney, D-Jackson, and Rep. Craig Fitzhugh, D-Ripley.

It’s notable that the icitizen/Beacon poll gave us conflicting results on how Tennesseans feel about the state’s economic development initiatives.

Nearly 70 percent disagreed that “state government should give your tax dollars to certain businesses in the form of handouts,” leading one to believe that citizens don’t approve of incentive grants.

On the other hand, in a different question, 59 percent favored the statement “It makes more sense for Tennessee to give more money to certain companies that show greater potential for job creation and growth” over the statement “Tennessee needs broad-based tax reform that lowers taxes for all businesses.”

But if it’s a little murky about what Tennesseans think is the right way for government to stimulate an economy, you might excuse them for the scarcity of information about the state’s programs to begin with.

On that, I think everyone has agreed.